stopmo

you are here [x]: Scarlet Star Studios > the Scarlet Letters > stopmo

September 5, 2012

adobe premiere & animation frame rates

by sven at 1:12 am

Earlier this year I finally broke down and purchased Adobe Creative Suite 5.5 - Production Bundle. ...Only a week or so before CS6 was released — sigh. Happily, though, I did a lot of shopping around and managed to get a very good deal from SoftwareMedia.com.

The critical application for me was Adobe Encore, which seems to be the only good option for authoring Blu-ray discs from a Mac. Going into this, I didn't know that Adobe Premiere is the hub of the production experience in CS5.5. It's been interesting getting familiar with the software.

The only film editing software I'd worked with previously was iMovie — and I kind of hated it. Premiere, on the other hand, is a pleasure. I particularly enjoy editing to music: looking for the best moments in my library of film clips, and finding ways for the visual beats to coincide with audio dynamics.

I've spent a lot of time watching instructional videos in order to get up to speed. (Google "Adobe TV" for the best starting place.) But now that I've begun to get my legs under me, I really appreciate some of the professional magic tricks I can work. The most crucial of these is converting frame rates.

Converting framerates for the NW Animation Festival

I'm going to oversimplify: video in Europe is 25fps, film in the USA is 24fps, and TV/DVD video in the USA is 30fps. If you tell a computer to convert one frame rate to another, it's just going to insert or delete frames — which creates a very noticeable stutter. (Unless you interlace — which is a whole 'nother nightmare.) ...What to do?

Well, first off, I've got a big advantage because I'm dealing with animation. Live action filmmakers often shoot footage in 30fps. Only a very tiny minority of animators originate films in 30fps. We work and think in 24fps. When our films get transferred to 30fps for TV/DVD use, they get degraded in the process. In the world of animation, we want to avoid 30fps if at possible.

Happily, we've finally entered an age where we can avoid 30fps. Blu-rays and broadcast HDTV can accommodate 24fps. 30fps is still in usage — but there's real movement toward 24fps becoming a universal standard for film and TV.

So, based on what's native to animators, and in hopes of a universal standard, I've settled on 24fps as the master frame rate for the NW Animation Festival. In the upcoming year, I'll be encouraging animators to send me their original source files — which are most likely 24fps — and strongly discouraging them from burning playable DVDs.

This still leaves the issue of how to work with 25fps. (Q: Where did that number 25 come from? A: It's an artifact of European electrical current being 50hz, whereas ours is 60hz.) After a lot of research and a good tip from the Steve Herring at Proludio, I've settled on this strategy: slow the films down by approx. 4%, and pitch shift the audio up by +.75dB. The change in speed is imperceptible, and no frames are lost.

In the context of Adobe Premiere, one uses the "interpret footage" menu to play back individual frames at a different rate. Audio needs to be adjusted in Adobe Audition. Once you find the settings and grasp the underpinnings, the conversion is fast and easy. Getting to the point of understanding why this is the right solution, and how to accomplish it — that was decidedly not easy.

posted by sven | permalink | categories: nw animation festival, stopmo

June 9, 2012

armatures 101 - part 2: how to make a wire armature

by sven at 9:42 pm

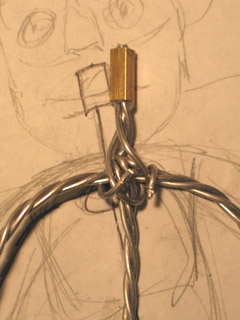

Here are videos from three well-respected StopMotionAnimation.com members, each describing how to build a basic wire armature.

(Click on name to go to their website.)

Nick's puppet-making series:

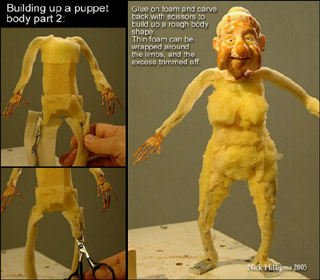

• Make a Buildup Puppet

• Tie-downs Tutorial

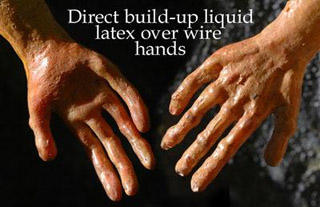

• Stop Motion Puppet Heads Part 1: Latex Build-up

• Stop Motion Puppet Heads Part 2: Mouldmaking and Casting in Silicone Rubber

.

.

MARC SPESS

Marc's puppet-making series:

• How to Make Wire Armatures for Stop Motion

• Stop Motion Puppet Construction 1st Edition

.

.

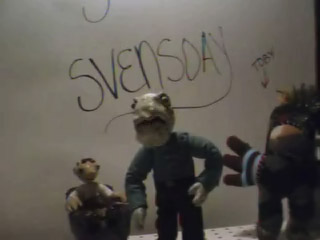

RICHARD SVENSSON

Richard's puppet-making series:

• Building a Stop Motion Monster: Making an Aluminum Wire Armature (1 of 4)

• Building a Stop Motion Monster: Making the Latex Skin (2 of 4)

• Building a Stop Motion Monster: Padding the Body (3 of 4)

• Building a Stop Motion Monster: Finishing the Puppet (4 of 4)

posted by sven | permalink | categories: stopmo

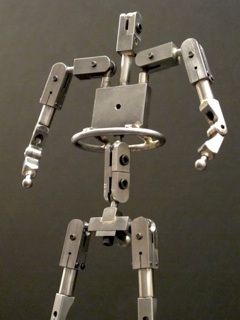

armatures 101 - part 1: wire vs. ball & socket

by sven at 5:06 pm

[Today StopMotionAnimation.com got a major overhaul and years of archives disappeared. I'm doing some writing to help repopulate the site with info useful to newcomers.]

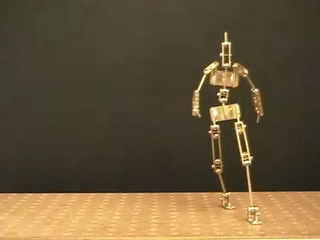

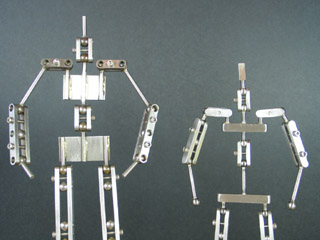

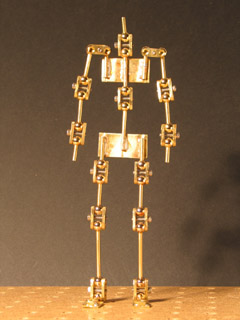

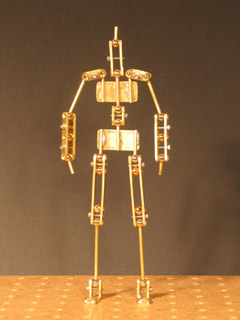

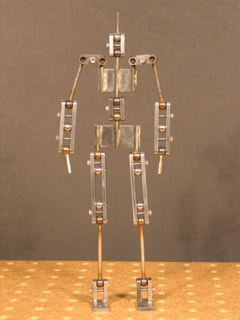

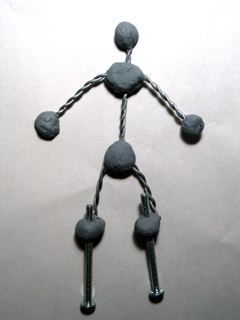

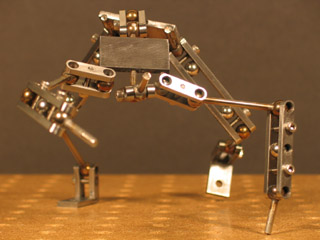

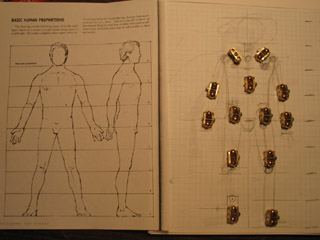

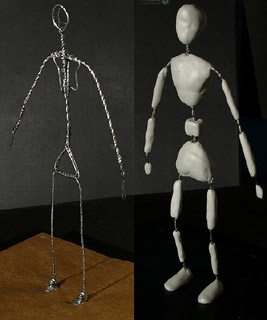

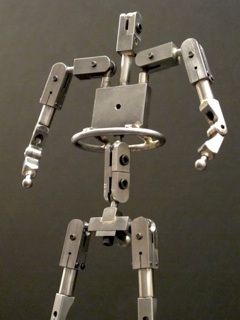

There are two main varieties of armature: wire and ball & socket. Here are the pros and cons.

1. Price

Wire armatures are inexpensive: ~$20 for materials. Ball & socket armatures are expensive: ~$150 for a humanoid kit, ~$500+ for something custom-built.

2. Time Spent Building

Wire armatures are fast to make (1-2hrs). Ball & socket armatures take a long time (30hrs+).

3. Durability

Wire armatures break. It's not a question of if—it's a question of when. A well-built wire armature can hopefully last for 5-minute film. A well-built ball & socket armature will never break; however, screws that keep the joints tight can become loose and need re-tightening.

4. Spring Back

When you bend a wire armature into position, it will "spring back" a little. A ball & socket armature won't spring back, and thus allows you to put a puppet into a pose more precisely. If you use framegrabber software, you can compare frames and compensate for spring back—so it's not such a big problem nowadays.

5. Hinge Motion

When you make an elbow using wire, the joint bows rather than hinging on a precise point. If you try to narrow the length of wire at the elbow joint, risk of breakage increases. With a ball & socket armature, you can make a joint that bends at a single, precise point.

6. Flexibility

It's a simple matter to make a tentacle using wire. It's very difficult to create enough ball & socket joints to simulate the same thing.

7. Limited Range of Motion

In ball & socket armatures, range of motion is often limited—especially at the shoulders. It may be difficult to transition a puppet between certain poses. For example, many puppets will lock up if you try to move from arms down at sides to arms up at sides to arms outstretched in front. Wire armatures, by contrast, can give you an unlimited range of motion. Constrained motion can sometimes make your job easier while animating... However, extra range of motion can also be very valuable. It might allow you to cheat your way out of a problematic pose on set.

8. Professionalism

There's a misconception that professionals only use ball & socket armatures. Not true. Most puppets made for TV use wire armatures. The expense of creating ball & socket armatures is usually only justified for feature films.

Bottom Line

Animating a well-made ball & socket armature is like driving a Porsche. It's a pleasure to work with, and you get the very best results. Expect to spend extraordinary amounts of time and money for that experience, though. A bad ball & socket armature is miserable to work with, and worse than a typical wire armature. You'd be wise to start off your animation career by learning to do good work with wire.

posted by sven | permalink | categories: stopmo

April 27, 2012

stopmo interview with elizabeth carmona

by sven at 2:40 am

Elizabeth Carmona, a graphic design student in El Salvador, is doing her graduation thesis research on stop-motion. She found my work via StopMotionAnimation.com and asked for an interview. I have a hard time saying no to pontificating about the subject — particularly if it might help an emerging artist — so here's what came of it...

Eliza: Thanks a lot for your answer and for agreeing to help me!

I'm doing a guide about "How to do stopmotion animation", and I was reading your site and it has such a wonderful information about the technique (I specially find really useful and interesting the essay about pros and contras of cg, and the aesthetics of stopmotion) and the way you've been experimentating with armatures.

So for the interview I wanted to ask you:

Why did you choose stop-motion?

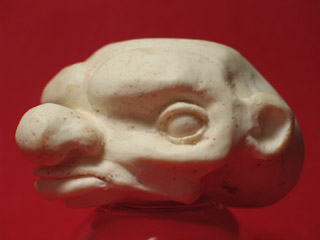

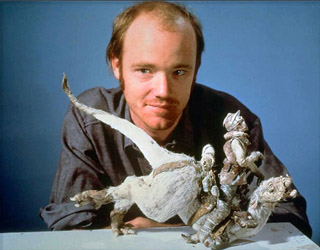

Sven: Stop-motion is something that I've wanted to do since I was maybe 6 years old. I read books about animation and special effects because I was in love with Star Wars and films like it. But animation seemed impossible then. I just couldn't see myself shooting on film and then having to send it off for developing. In 2002, one of the books I'd read as a child — The Animation Book, by Kit Laybourne — was republished with new material about computers. Suddenly it dawned on me: all you need now to do animation is a computer — and I've already got one of those. So I started doing motion graphics and kinestasis using AfterEffects. But it still felt like something was missing. I enrolled for a hands-on class about shooting Super8, so I could say I'd at least tried using celluloid. In the process of doing that, I finally got my chance to try stop-motion. And when I did, I was hooked. It was like a fever. For at least a year, it seemed like I did nothing but study stop-motion and experiment with puppet-making materials. I could talk about the various things I love about stop-motion — how you're making real, tangible objects come to life (magic!) — but the attraction goes beyond reason. I bonded with stop-motion at a young age, and late in life am unable to shake its gravitational pull.

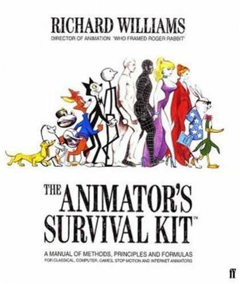

Who have been your influences?

I fell in love with Star Wars, King Kong, all of Ray Harryhausen's films... There's a lineage there, that goes from Willis O'Brien to Uncle Ray to Phil Tippett. But while the sci fi / fantasy stuff is ingrained in my bones, it's actually the more stylized, artsy puppet animation that I'm interested in making myself. There's another lineage: which goes from Vladislav Starevich's The Cameraman's Revenge to George Pal's Puppetoons to Henry Selick's The Nightmare Before Christmas. In the current scene, I'm most inspired by folks like Jeff Riley (Operation: Fish), Neil Burns (The Nose), Nick Hilligoss (L'Animateur), and Barry Purves (Tchaikovsky - an elegy).

From where do you take inspiration for a new story or character? what comes first for you?

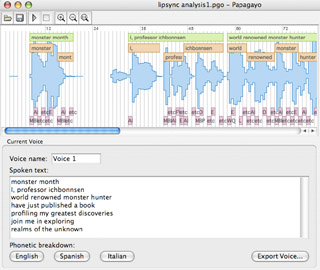

I'm very interested in process. Story and character are important, but pretty much everything I've done so far has begun from wanting to tackle a specific technical challenge: such as lipsync or replacement faces. Time has also often been a consideration — challenging myself to make a film in a set number of days or weeks. I find that by starting with the limitations I want to obey, I'm less likely to get sucked into attempting a project that's too big to be completed in a tolerable amount of time.

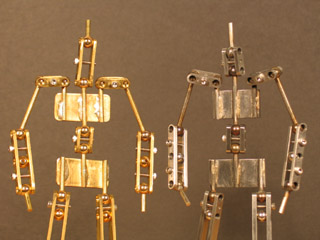

While making the puppet, what are the most important things you consider?

A puppet is only as good as its armature. To get really nuanced movement, you want to have a ball and socket armature. So I've spent a lot of time learning how to create professional-level steel armatures using a milling machine and lathe. Armatures are interesting to me as an art form unto themselves, though. Most puppets I've actually animated — and truth-be-told, the majority of puppets in professional studios — have wire armatures. Frankly, the benefit of being able to create a puppet quickly is usually more important than having one that's perfect.

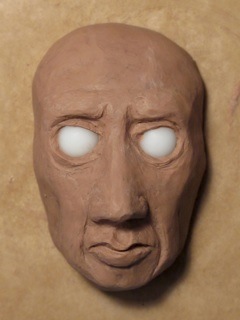

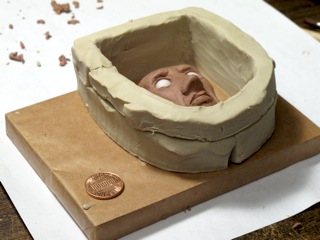

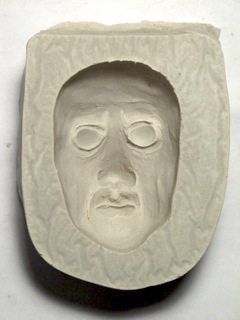

Besides the armature, I also want puppets that have a very sculpted look. With build-up puppets, you can do a lot with hard body parts made from Super Sculpey or epoxy clays (such as Magic Sculpt, Milliput, or Apoxie). Given the look I want, though, I'm naturally drawn to mold-making and casting puppets in foam latex or silicone. I've had some successful experiments, but am still in working on really learning the skills.

What materials you prefer to use and why?

Every material has a place in the puppet-maker's toolkit. A puppet's head might be made from polymer clay in order to gain more working time while sculpting — whereas the hands and feet might be made of quick-curing epoxy (much stronger) to avoid being broken, since they're so close to high-stress joints. For humanoid puppets I like to use hard parts whenever possible, so that I don't have to fuss with re-sculpting soft clay mid-shot. But, on the other hand, I also like working with clay on its own terms. I think that animating with clay can be like having a 3-dimensional sketchbook... It allows you to improvise and explore ideas in ways that build-up and cast puppets don't. For any kind of artist, I think it's important to make improvisation a regular practice. Make elegant puppets — but also play with shapeless blobs. Ultimately, I think it's good to avoid getting stuck in one set of materials; you should strive to have all of them at your disposal, and know which is right for a particular job.

In your point of view, how does social media and technology influence modern stop-motion animation?

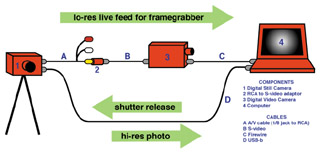

Stop-motion has undergone a technological revolution in the past 15 years. With the advent of frame-grabbing software, animators have the ability to toggle back and forth between frames, making sure that they're getting the shot they want. Before this, animators used tools like surface gages (many still do) — but mostly had to rely on sheer mental focus to keep track of what bits were changing between shots. Subtle stop-motion is still challenging — but far easier now that you can check your work before committing.

The internet and forums such as StopMotionAnimation.com and AnimateClay.com have also played a huge role in stop-motion's renaissance. It used to be extremely difficult to find good information about how to make our specialized puppets. Now there's an active online community where masters and amateurs co-mingle, solving problems and learning from one another. Some of the magic may have been lost in the process of revealing the art form's secrets — but as a result, an art that once seemed on the brink of extinction is prospering again.

I think stop-motion is particularly suited to communal discussion, too. With computer animation, it can be challenging to explain what's going wrong with your software. Stop-motion, by contrast, is all about craft projects. "Show and tell" is much more intuitive when you're working with real, tangible materials like clay and wire and foam.

The web is a godsend for stop-motion animators as people. It's difficult enough to find in-the-flesh communities of animators. When you do, stopmoes are usually a minority. Being able to Google "stop motion" and find a bunch of people doing the same sort of work breaks the isolation — and then allows friendships to form. My most valued circle of stopmo friends is made up of individuals living in Los Angeles, San Diego, New Orleans, Atlanta... While I'm all the way up here in Portland. We keep up with each other via show-and-tell on our blogs, through "hey, have you seen this?" emails, and the background noise of Twitter. We've kept tabs on one another during hurricanes and earthquakes, when there's a medical crisis, or when someone just goes missing for a while. ...But of course, that story of "internet relationships extending into the real world" has been true for many types of online affinity groups, not just our own.

Technologically, the most curious thing to me is seeing stop-motion beginning to become indistinguishable from computer animation. The advent of rapid-prototyping 3D printers means that objects for stop-motion are being created first in the computer, then translated into real sapce. Motion control cameras allow dizzying moves that were the sole purview of CG not long ago. When Coraline came out, the stop-motion community seemed torn about how to feel... On the one hand, the technological accomplishment was unprecedented. On the other, the quirky jerky movement usually associated with our hand-made films seemed to be disappearing.

Since Coraline, rapid prototyping technology has spread rapidly among professional stop-motion studios... And it looks like LAIKA's follow-up to Coraline — titled ParaNorman — will push the limits of technology even further. I have no crystal ball — but it seems like in the near future, most of what CG can do (with the exception of large crowd scenes) will be able to be accomplished in stop-motion with nearly identical results. Then what? ...Frame-by-frame hand-drawn animation has been on the wane for a while — perhaps it will have a resurgence. We crave uniqueness. Just as with stop-motion, what's currently being ignored will soon start to look fresh and new.

posted by sven | permalink | categories: stopmo, writing

July 20, 2011

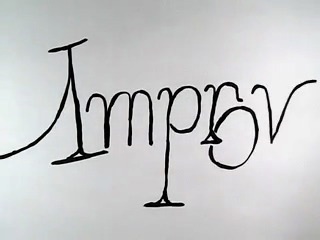

animation walk

by sven at 5:30 pm

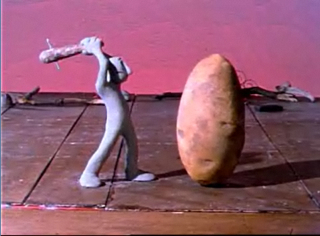

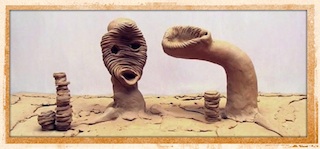

Experimental stop-motion animation driven by six principles:

- An animator animates.

- You can animate anywhere.

- Get out and walk.

- Every artist needs a sketchbook.

- Clay is your pencil — the photo is your page.

- Watch your mind evolve one frame at a time.

...It's been such a busy year, I had to find some way to squeeze in actual filmmaking!

P.S. As usual, the soundtrack won't be much good unless you've got decent woofers in your audio system.

posted by sven | permalink | categories: movies, stopmo

July 13, 2011

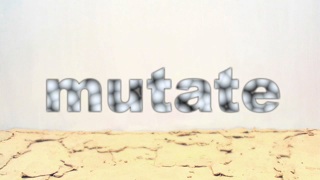

"mutate" in da vinci days film fest - july 16, 17

by sven at 1:46 pm

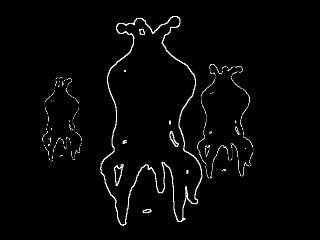

My short film Mutate will playing at the da Vinci Days Film Festival this weekend in Corvallis.

It's playing twice, so Gretchin and I will be taking a little vacation to check out the whole affair. It's part of the Animation Block, which will show on Saturday (July 16) at 3:45pm at the Darkside Cinema and Sunday (July 17) at 2:30pm at the Majestic Theatre.

I'm often amused by how festivals re-write my film description. Here's the da Vinci version:

Like an Animal Planet documentary from another dimension, MUTATE reveals the bizarre life-cycles of various alien creatures as they meld, merge, dissolve and evolve in surprising and frequently hilarious fashion.

Not bad. :)

posted by sven | permalink | categories: exhibits & events, movies, stopmo

July 3, 2011

ken sipel visit

by sven at 4:00 pm

Ken Sipel is a fellow stopmoe and blogger. Last month I had the pleasure of meeting him in-the-flesh.

Ken was coming through town and contacted me to see if we might meet up. Absolutely! I love it when stopmo bloggers bridge the cyber divide — and encourage other readers to also come visit if they're near Portland.

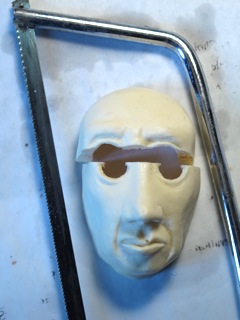

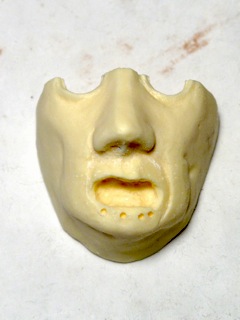

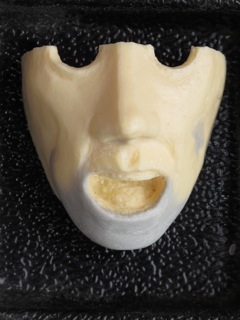

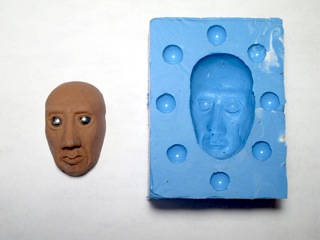

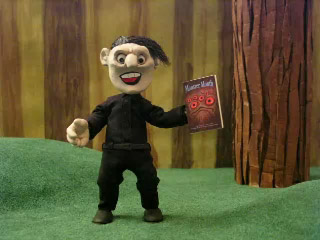

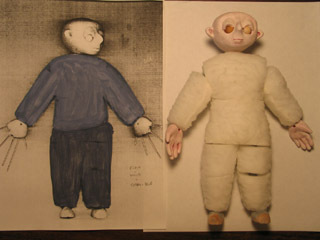

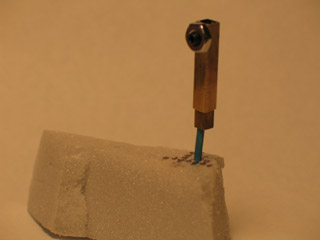

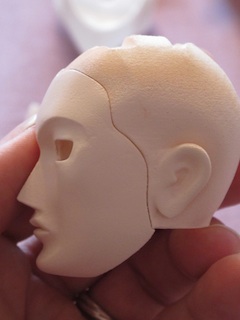

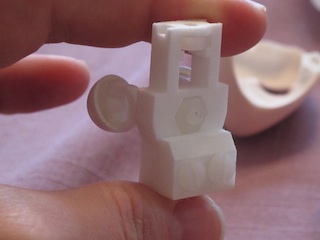

We talked about the NW Animation Festival and about my armature work. Then Ken gave me real treat, and let me see the work he's been doing on 3D-printed replacement faces for his puppet "Christian."

Since Coraline, a number of us have been speculating that indie animators might print puppet faces in resin using shapeways.com. To the best of my knowledge, Ken is the first to actually try it.

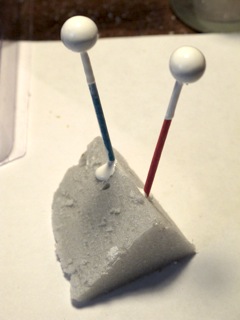

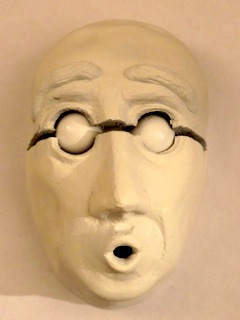

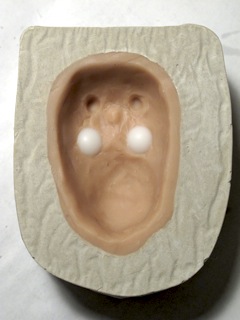

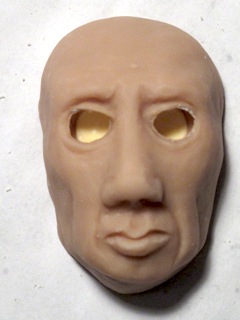

The photos that I took at the Coraline premiere party were apparently quite helpful in the design process. In the photos here, you can see that the puppet head is built from four main parts: the back of the head, the face mask, a core, and the eyes assembly.

The back of the head attaches to the core with a screw at the top, which will later be covered by hair. The contours of the core could theoretically be rectangular, but become narrow at the jaw to allow a tight fit with the back of the head. The face snaps into place with tiny magnets.

The core has a detachable part at the bottom that clamps around an armature's neck post. The eyes are half-spheres with tiny ball joints held in place by the pressure of the semi-flexible plastic sockets. The whole eye assembly can be detached from the core.

Congratulations to Ken on this ingenious puppet construction! I am thoroughly impressed with how his project CRS Glimmer is coming along, and can hardly wait to see further developments. Outside of feature films and big budget TV commercials, this is pioneering work!

posted by sven | permalink | categories: stopmo

July 1, 2011

notes on brazing

by sven at 7:00 am

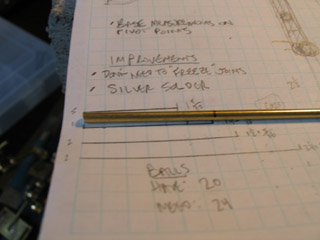

I'm still not as proficient at brazing as I'd like to be. So I want to capture some notes, while this last project is still fresh in my mind.

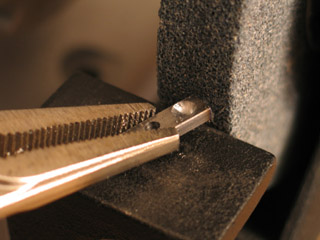

1. CUTTING SOLDER

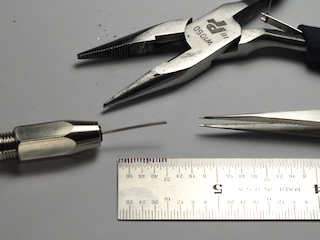

When cutting solder, you want five tools on hand:

- pin vise for holding the solder

- ruler for measuring

- fine-tipped sharpie for marking

- pliers for cutting

- needle-nosed electronics tweezers for picking up bits

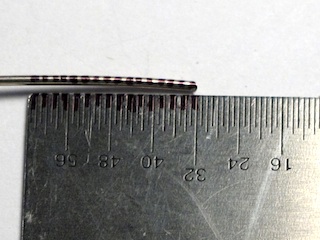

I'm using 1/32" diameter Safety-Silv 56 cadmium-free silver solder. Smallparts.com is supposed to carry it, but right now they're out and don't know if or when it'll be back in stock. It's hard to find, so I'm wondering where I'm going to get some more.

When cutting the solder, I try to look at the wire in terms of 1/64" increments. I have to wear optivisors (magnifying glasses) just to be able to see these measurements clearly. Blackening every other increment on the ruler helps. I can basically draw a line straight from these marks onto the soldering wire.

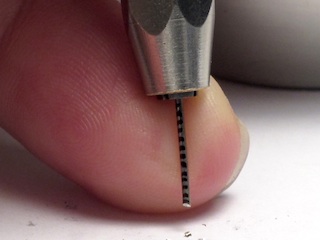

The pin vise is a new discovery. It makes holding wire while cutting very much easier. It also allows me to make cuts a good deal closer to the tail-end stub of the wire segment.

I've used the electronics tweezers before, but they really proved their worth on this project. I originally bought them for removing microscopic splinters from my fingers. I really ought to get a second pair now, to be dedicated to general shop work.

When cutting the wire, keep the pliers flat against the table. That way, the wire will get trapped underneath, rather than flying across the room. The cutting edge isn't in the middle of the tool — it's closer to one side. If you take advantage of this, you can easily cut 1/16" bits of solder, which are sometimes useful. Note, though, that the cutting action will cause the wire to be pressed down and gouge the table. Be sure to put down a self-healing mat.

When solder bits have been cut, don't presume they're all equal. Use your eyes. A 1/32" bit of solder will look roughly square. Visually gauge whether the piece of solder you're picking up is 1/64", 1/32", 3/64", or 1/16".

For 1/8" balls, I've found that 3/64" of solder works quite well. I've been putting 3/64" lengths into the ball holes… It might be wiser to put in three bits of 1/64" solder, so they can pack down into the hole. In a 5/64" deep hole, a longer piece of solder will prevent the rod from getting in — whereas bits can be stuffed in more compactly.

It would probably be wise to scientifically figure out exactly how much solder is required for any particular size of hole, so I stop guessing and thinking about it while doing work.

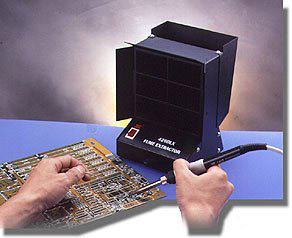

2. FLUX SAFETY

Safety first! Silver-Silv 56 is better than a lot of other solders which contain lead, cadmium, or antimony — but you still have to be thinking about the flux.

Harris brand flux contains fluorides, which can damage your lungs, and are absorbed through the skin. You might not know at first that it's gotten into you; this stuff causes subcutaneous chemical burns. So get used to wearing nitrile gloves. Don't go with latex; remember that it originally comes from rubber trees, which as an organic material is nearly as vulnerable as you are.

For flux fumes, go with the 3M 6003 respirator cartridges, which handle organic vapors and acid gas. These cartridges specifically mention fluorides as one of the chemicals shielded against, whereas simple organic vapors cartridges (6001) do not.

Even while wearing the respirator, be actively moving fumes out of the room. I've moved to a two fan set-up. One fan is set up at the window to pull fumes out. The other is set on the other side of my work table to push air towards the window. It gets a bit loud, which is why I wear the protective headphones.

3. BRAZING ON FLAT SURFACES

On this past project, I needed to braze rods to rings. It seems like most brazing set-ups are either vertical or horizontal: either laying flat on a table, or held upright in a vise.

I'm using a ceramic tile bought from a jewelry supply store which is specifically designed to withstand open flames. Several years back I simply used a cinder block. I don't know if that was a good idea, or if I just got lucky with the stone not exploding. Either way, this is a much more elegant solution.

I think these posable tweezers are called "helping hands" — though there's another tool that possibly also goes by that name. It's good to keep at least four of them on hand for putting things in position. A brass rod turned out to be useful for poking at things if they started moving while under the flame.

I still have to remind myself each time I do a new project: solder will only flow where there's flux. I'm beginning to think that you can't over-flux a part. For a while I was skimping on flux, because it seemed to leave bad black residue on parts. I think now, though, that the problem was that I overheated the parts, actually burning the metal. I probably wasn't using the right pickling compound back then, either. You need Sparex #2 to effectively remove flux residue from ferrous metals.

I did a bunch of shopping around to find appropriate jump rings. Ones with brass or steel cores worked fine, regardless of whether they were plated. Ones with "base metal" cores melted into a mess. It turns out that "base metal," used commonly in the jewelry industry, is composed largely of tin and zinc… The very same things you find in low-grade solder!

I've had a bad habit for a long time of quenching parts in water after they've been brazed. I'm making a concerted effort now to do the right thing and let them cool slowly. I think I just need to have a second ceramic tile for cooling. That way, valuable work space isn't being eaten up while I wait. Drawing a grid on the tile to help me keep small parts lined up also made the process feel better organized.

4. ERGONOMICS

The horizontal brazing work had me looking down at the table for hours on end. My neck is still in a lot of pain days later. I'm interested in re-working my ergonomics.

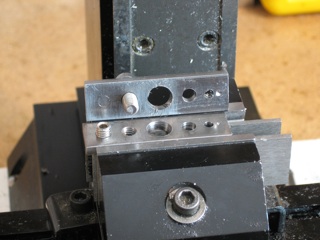

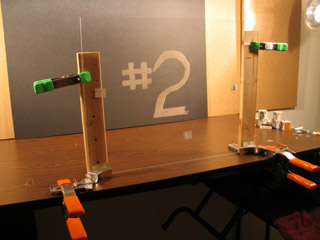

Regular tables are about 30" tall. Jewelers, who have to work with very small parts all day have special benches that are ~36"-39" tall. Back when I was working on the tiny Mi-Go maxillipeds for The Whisperer in Darkness I built myself a small jeweler's riser that clamps onto a normal work table. It's been absolutely great so far — and I think I can still do more to optimize the design.

The riser gets more useful when combined with other things. I got a number of steel trays from a restaurant supply store; clamping one onto the riser gives me a nice rim to keep little parts from rolling off. Clamping a vise onto the riser also helps bring my work up to a comfortable height.

For the Mi-Go armature, I was doing crazy-small work with 000-120 screws. I had to come up with complicated strategies just for holding these things… For instance, putting a pin-vise into the larger vise, held between rubber jaws.

I re-configured the riser slightly on this last project. Besides having the vise on a different side of the riser, the main addition is a small bin located just beneath it, to catch tiny parts if they should fall.

This set up is good for vertical brazing, but it's not wide enough for the ceramic tiles if I want to do horizontal brazing. I'm considering making a wider jeweler's riser for that. (My neck may thank me.)

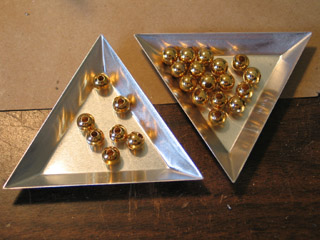

5. BRAZING BALLS

My method for brazing balls hasn't changed much — but I'm really thrilled to have found some better tools for moving solder bits and flux.

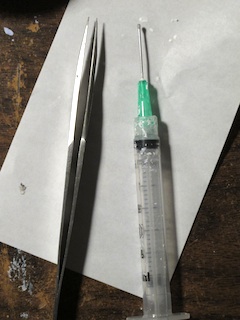

I've already said it: electronics tweezers, FTW. The other discovery is that I can make flux paste a bit more fluid with water, then deliver it where it needs to go using a syringe. Before, I was using tooth picks, which was clumsy and miserable. What's more, I'd need to leave the jar of flux open; the paste dries out quickly. Keeping the flux in a syringe keeps it good and wet.

Flux paste seems to be water-based. Just use an eye-dropper to mix it with a little extra water in a small jar. Then it sucks up into the syringe easy as pie. (I should mention: I grind off the pointed tip of the syringe with a belt sander before doing this.)

As always, I've got the rod clamped into a vise, and am holding the ball down with a hammer while it's heated. (Hot gas will make the ball want to pop off.) The hammer isn't an ideal solution, because it's also a heat sink cooling off the area that you want hot. I need to look into other tools for this job.

There's a temptation to loosen the downward pressure on the ball, in order to let it heat up more quickly. Bad idea. The ball starts to rise, and then when you press it back down, molten solder squirts out in blobs. Keep downward pressure constant.

Lionel Orozco says that the ball should be heated to a cherry red. Jeremy Spake tells me that this may actually be too hot — that you should specifically avoid getting to the cherry red stage. This matches my experience. I've seen in welding books that there are names for all the various colors that steel turns while being heated, and they are indicative of specific temperatures. I'd like to do deeper research at some point to truly understand how the color of the ball and the melting point of the solder match up.

Jeremy also suggests that the entire ball can be covered in flux. Very interesting! If I'm not overheating my metal, this might work out really well. Must experiment.

I've moved my pickling station closer to the window. Duh. And I've put it on one of those metal pans, to protect the work table. Incremental progress.

On this last project, I was having trouble getting a nice clean seam of solder where the ball and rod connect. It was turning out too blobby, which would have impaired range of motion. So I decided to use less solder — to the extent of not having a visible seam.

The problem with this strategy is that without the visible seam, there's no way to know for certain that you got a good bond. It's a big no-no in armatures… And let me tell you: the very last thing you want as an armature maker is for a ball to break off mid-scene while an animator's working!

So I came up with a stress test. I put rubber jaws onto my vise, and clamped the ball tight. I twisted the rod using parallel pliers. If the bond is weak, the ball breaks off; if the bond is strong, the rubber will tear first.

I think it's a good test. The pressure of the vise — even with rubber jaws — is greater than what the part will likely experience when it's in a step-block joint. It's definitely greater stress than human hands can exert (a poor test). And the stress test is based on twisting, which is the only way balls are really likely break off. I broke enough bad joins, I feel reasonably confident that the survivors will hold up.

Even so… It's kind of a miserable process. I really want a better strategy for clean, small ball seams the next time I do this.

posted by sven | permalink | categories: stopmo

June 30, 2011

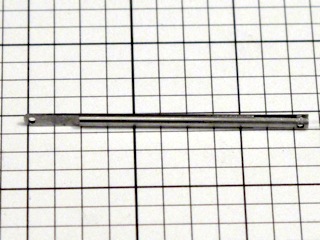

cutting rods to size

by sven at 7:00 am

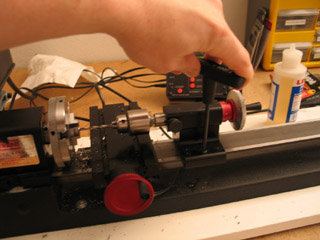

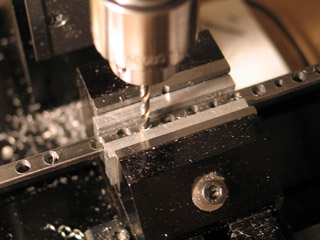

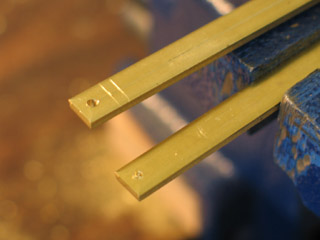

In making armatures, the smaller you work, the more you have to focus on precision. By the same token, when you start doing batches of more than 100 parts at a time, you start looking really carefully at each step of your process.

Rods are the simplest part of an armature. But during the past year, I've come to realize that they're as deserving of attention as any other component. Today I'm going to walk you through the process I've developed for making good rods… In excruciating detail.

Here are five guiding principles:

- Don't assume your rod is actually round.

Like in cooking, start with the best ingredients possible. I've moved to using type 303 precision ground rods, which are pretty close — but even then, while lathing you might discover a rod is .0005"-.0010" off on one side. - You can't get an accurate measure of length if the ends aren't flat.

Which means that before you can even check the length of a rod, both ends need to be lathed. - Protect your lathe's collet by chamfering rod ends.

You may not be able to see burrs on the end of your rod, but you'll feel them scraping the inside of the collet when you try to shove it in. Collets are precise tools; take care of them. - You can't put a rod in a hole of the same diameter.

If your rod is precisely 1/16" wide, and the hole it's supposed to go into is precisely 1/16" wide, the rod won't go in. You have to narrow the rod just slightly, so there'll be a little bit of play. - Don't keep numbers in your head.

When machining big tedious batches of things, trying to remember numbers will inevitably lead to error. Write things down instead.

OK… On to the step-by-step instructions. When you get good at it, this should take about 7-9 minutes per part.

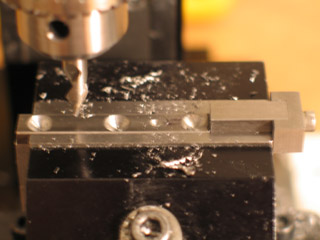

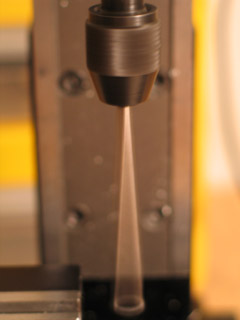

Step 1: Rough cut your rod into segments

Start by marking the rod you're going to cut with a fine-point sharpie marker. Cut it into segments using a 1/16"-thick abrasive wheel on a mini cut-off saw. These things only cost ~$25 at Harbor Freight, as opposed to ~$60 at Micro-Mark. Great tool. Wear a tight-fitting face mask — you definitely don't want stainless steel dust in your lungs.

Step 2: Chamfer one end of the rod

One end of your rod segment will be fairly smooth, the other will have a big burr hanging off it. Prep the smooth side to go into the lathe by filing the edges. I find it useful to put the rod into the chuck of hand-held electric drill, and simply run it across a stationary file.

Step 3: Flatten one end of the rod

With one end of the rod chamfered, insert it into the lathe collet. If you're trying to work precisely, don't use a jawed chuck — it's just not as accurate. Lathe that big ugly burr right off.

Step 4: Chamfer and mark the flattened end

The end of the rod is flat, but there are still microscopic burrs on the edges. While the segment is still in the lathe, use a tiny diamond file to very slightly soften that edge. While you're at it, use a normal-sized sharpie marker to blacken this end of the part. It's helpful as you go through the process to be able to tell one end of the part from the other.

Step 5: Flatten the other end

Take the segment out of the collet and turn it around. Repeat step 3 and flatten the other end of the rod.

Since you've blackened one end of the rod, you don't have to bother chamfering this side. Just make sure that when you do further work on the rod, it's always this side that you're cutting.

Step 6: Measure the part

Using digital calipers, measure your part to see how long it is. Hopefully you've left yourself ~.0100"-.0800" of extra length, since we're still going to need to lathe the part to its final size.

Step 7: Write down the measurement

However long the part is, write that number down on a little scrap of paper. If you're doing a big batch of parts, I recommend getting yourself a cheap jewelry organizer (~$3) to use as a palette.

I've got a 3/4" square paper punch that came from a craft supply store — very useful for making the tiny bits of paper. Card stock works a bit better than typing paper, because the paper doesn't bend when you lean it against the walls of the jewelry organizer.

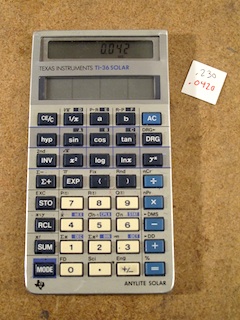

Step 8: Calculate how much to shorten the rod

For the rod we're looking at below, I wanted the final length to be .1880". Since the rod at this stage was .2300" long, I just needed to subtract to figure out that I needed to remove .0420".

Step 9: Write down how much the rod needs to be shortened

On the same tiny square of paper, write down how much the rod needs to be shortened. I find using a red pen here helps keep the new number visually distinct. Anything that helps prevent errors is good!

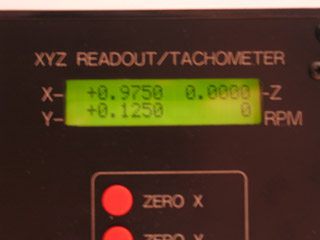

Step 10: Locate the end of the rod

Put the chamfered end of the rod segment back into the lathe. Blacken the flat end of the protruding side with a normal sized sharpie marker. Bring your cutting tool in until it just touches the end. If you're careful, you should be able to remove less than .0005" of material while doing this. Listen for a change of sound when the tool touches the spinning rod, and look for whether or not the sharpie ink is being rubbed away.

Step 11: Cut the rod to its final length

Zero out the DRO (Digital Read Out). Use the lathe to cut off the amount of material that you wrote down in red. For 1/16" rods, I found that .0050" cuts worked well. You can take off more at a time safely — but the stress is more likely to cause the rod to move in the collet.

Step 12: Check that you hit the correct length

Sometimes things go wrong. Like when a rod moves in the collet, and you don't actually cut off as much material as you thought. Check your work with the digital calipers. In the photo below I was off by .0005" from my desired length of .1880". That was a perfectly acceptable level of error for this project.

The part is now at it's correct length.

Step 13: Position the rod for trimming its diameter

If this end of the rod is going to go into a ball, then you're going to need to trim its diameter. I find lathing about .0010" off all around gives just enough play to get the rod into the ball's hole while still keeping a close fit.

For this project, the ball holes were 5/64" deep (.0780"). I decided the diameter trim should be .0850" long. I wanted the rod to stick out .1000" from the surface of the lathe collet, so there'd be a margin of safety between the cutting tool and the collet. To accomplish this, I created a little tool that allows me to push the rod into the collet to a (reasonably) precise depth. Using the .1000" tool, position the rod in the collet.

Step 14: Zero out the DRO where you want the diameter trim to end

As in step 10, blacken the end of the rod, and carefully bring the cutter in until it just touches. Zero out the DRO. Without performing a cut, move the cutter along the Z-axis to .0850". Zero out the DRO again.

Now, when you're trimming the rod ends, all you have to do is travel to zero each time. It saves a lot of brain power. (If you're doing a big batch of parts, you're only going to have to do this step once.)

Step 15: Locate the side of the rod

Blacken the side of the rod. Move the cutter on the X-axis and watch for when it makes a mark in the ink. Figure out where the edge of the rod is and zero the DRO. Move the cutter in to X=-.0010. You're now ready to make cuts. (For a batch, you're only going to have to do this once.)

Step 16: Trim the end of the rod

With the cutter set at X=-.0010, move it to Z=0, and then back off from the part on the Z axis. Leave the X alone. Test the trim by placing a ball on the end of the rod. If it fits nicely, then you're done — or ready to trim the other end of the rod.

There, that wasn't so hard, was it?

Oh… I guess it was. Well, at least you've got a really great part to work with now. ;-)

posted by sven | permalink | categories: stopmo

June 29, 2011

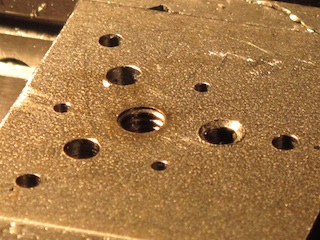

evolution of the ball-drilling jig

by sven at 7:00 am

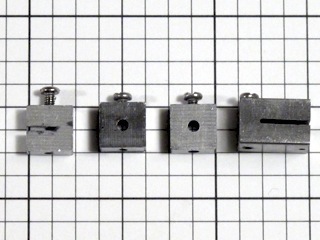

Drilling balls is a fundamental of armature building. It's a tougher problem than you'd think. At this point, I believe I've gone through seven methods of drilling balls — and I'm still not entirely satisfied.

Today I'd like to do a retrospective of the methods I've tried and discuss their various shortcomings.

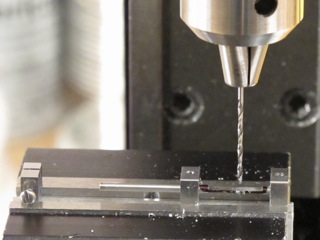

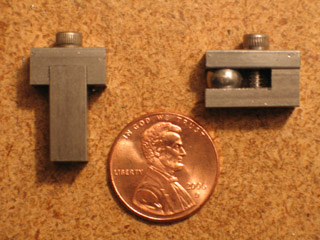

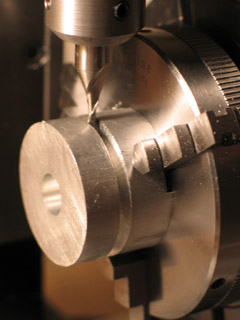

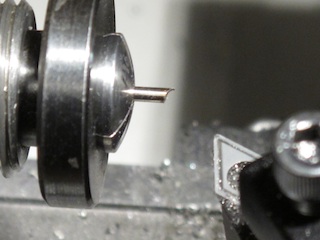

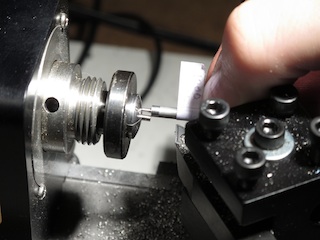

Fig.1: The classic method for drilling holes in balls is to put the ball in a lathe chuck. This is what I did for the Man of Steel back in 2006.

The advantage is that your hole should be perfectly centered. The big problem is that the drill bit wants to push the ball back into the chuck, ruining your control of hole depth. You can try to crank down on the chuck and make it really tight — but the stainless steel ball is harder than the jaws of the chuck and will leave a ball-shaped deformation. Oops.

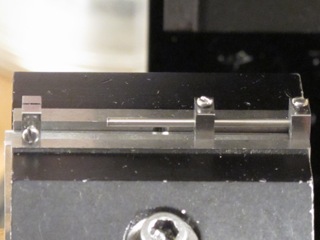

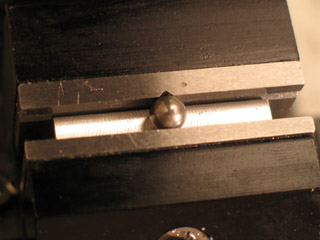

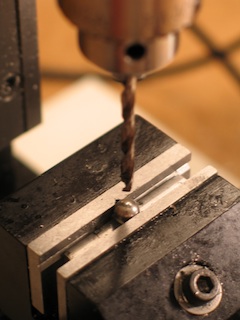

Fig.2: If you put the ball into a milling vise, supported by a riser, you can be sure that your depth will be accurate. However, now you're going to have to worry about getting the hole perfectly centered.

My milling vise has a nice built-in groove for holding the ball in place. But if you use it, where do you measure from to find the center of the ball? You can't use the fixed jaw because you don't know how deep the ball sits in the groove*. You can't use the moving jaw because milling vises pull that jaw down at an angle. If the jaw isn't vertical, there's no way to tell exactly where the ball is making contact.

(*Technically, you could figure it out with geometry — if there was a way to get really precise measurement of the groove's dimensions.)

Fig.3: I tried moving the ball over in the vise, so I could use the fixed jaw as a vertical surface to measure from. But with only two points of contact, the ball wants to spin on the Y-axis when the drill makes contact.

To give the vise a better grip, I tried making a grooved insert that attaches to the moving jaw. As I recall, it did an OK job of holding the ball in place… But then I discovered that the ball was deforming the vise jaws. Again, the stainless steel ball is harder than the things holding it. No good.

Fig.4: Thinking about sandwich plate joints, I created this jig that would hold two balls from the sides. Several problems… It's fussy to get balls in and out. You have to take the versatile milling vise off the XY table and put a bunch of effort into getting the jig parallel with the milling column. There's a lot of room for compounding errors if the jig itself wasn't milled perfectly straight. It's an overly complicated and irritating solution.

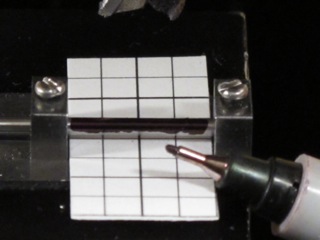

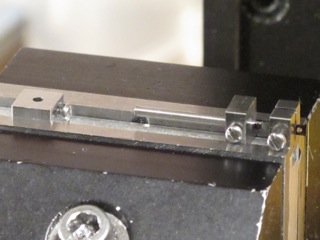

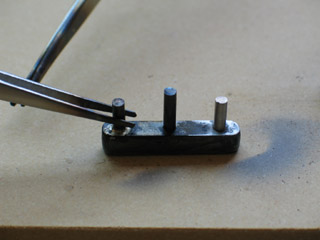

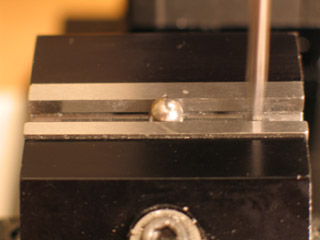

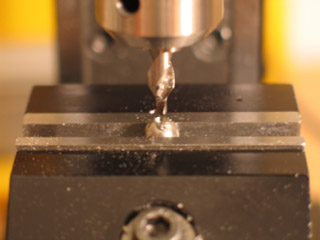

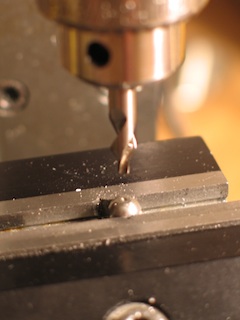

Fig.5: This jig was inspired by step-block joints, and worked pretty well most of the time. It involved a few superfluous steps, though. After clamping a ball in place, I'd fill the hole above it with oil. (The hole held the oil in place quite nicely.) I'd use a cylindrical diamond burr to grind a flat spot on top of the ball. I'd use a center drill to start a hole. Then I'd use a drill to make the actual hole. I've since found a method that doesn't require flattening the ball or using a center drill.

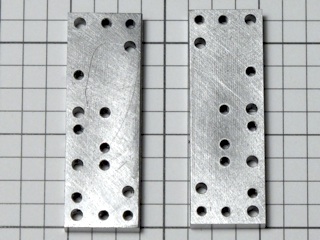

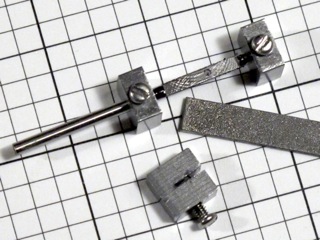

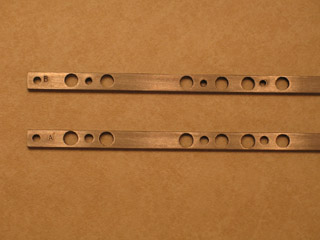

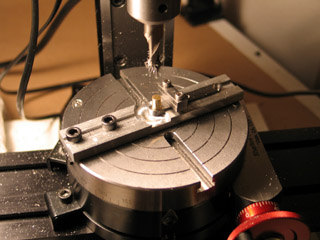

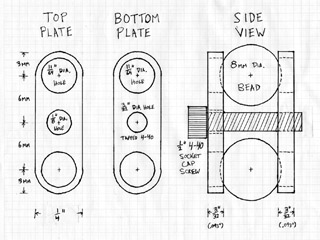

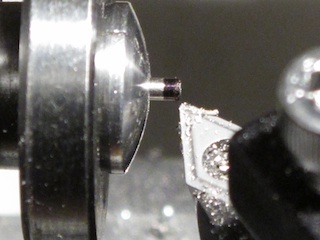

Fig.6: My most recent attempts take their inspiration from this jig by Jeremy Spake. The top holes guide the drill directly to the balls' centers, making center drilling unnecessary. This design is intended for use with a drill press. Unfortunately, I don't have a drill press with depth control that I really trust, so I've had to adapt it for the mill.

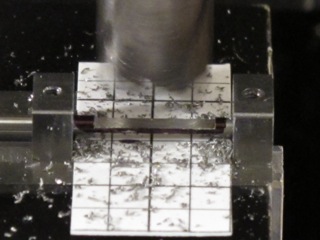

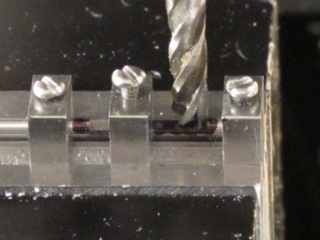

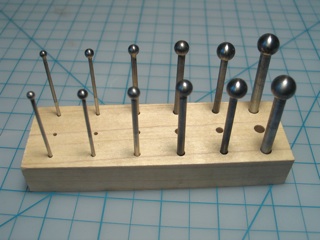

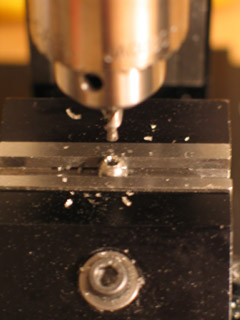

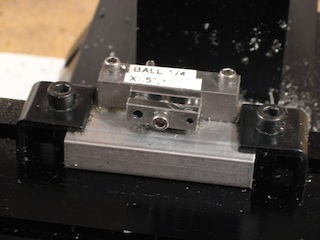

Fig.7: Using three balls guarantees that the top plate will be parallel with the bottom. The hole you make in the ball will be centered, the drill bit won't go into the ball at a funny angle, and you've got good depth control. Excellent!

My version for the milling machine theoretically gives me depth control down to .0005" accuracy. You do have to pull the drill out promptly, though, or else Z-axis backlash might allow the drill to keep going down after you've stopped turning the handwheel.

With Jeremy's design you can do a couple of balls per minute. With mine, you have to re-load the jig every time you want to drill a new ball. Slower… But I'm willing to give up some time for the sake of getting accuracy.

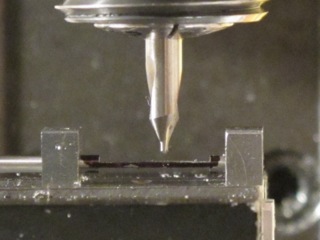

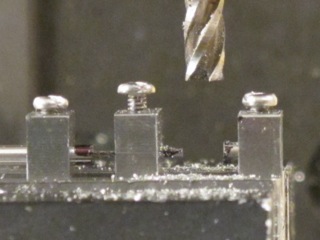

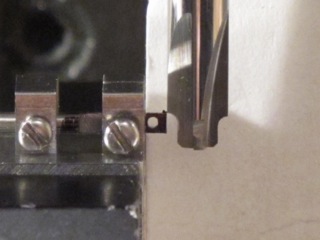

Fig.8: Much to my frustration, I've run into problems with this jig design becoming deformed. If your speed and feed for the drill aren't right, the ball will work harden and the bit can't cut into it anymore. After that point, the drill is simply smashing the ball downward into its seat.

Fig.9: The previous jig was made out of 1018 steel — just about the softest steel you can buy. For my most recent jig I switched to type O1 tool steel, which is harder than 302 stainless. It too has deformed with use, but it survived a much longer time. Progress.

I think the next improvement would be to mill ball cups into the jig… And to really control speed and feed. Unfortunately, I think the only way to achieve that is to purchase a CNC machine. A computer would stepper motors to precisely control the descent of the drill bit.

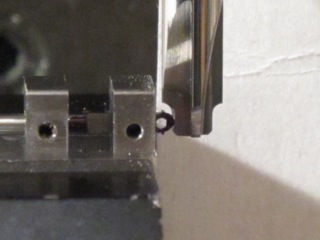

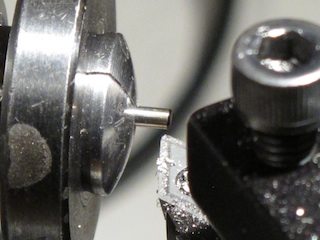

In the meantime, let's take a closer look at using the current jig design.

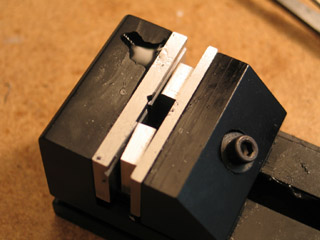

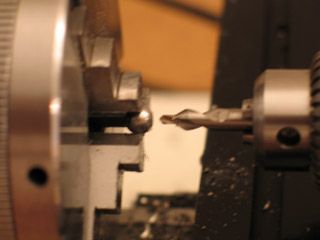

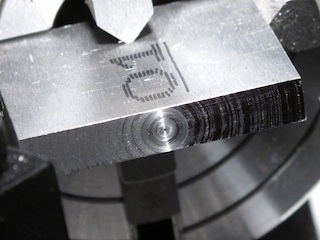

Fig.10: A blog post for another day would discuss the ordeals I've gone through trying to learn how to make the ends of rectangular stock truly flat. Recently I discovered a very simple solution to my woes: four-jawed lathe chucks.

I've been prejudiced against the lathe ever since I couldn't get it to drill balls correctly. Now I discover it's the solution to a problem that's given me countless headaches. Ironic? Anyway, this jig is my first time using the independent-jaws version of the four-jawed chuck.

Fig.11: When you put the smallest balls into this jig, they can fall through the larger holes if you accidentally knock them. It's a good idea to put tape or stickers over the larger holes while you work.

Fig.12: You can see here how parallel the jig's top and bottom plates are. When one of the holes starts deforming, the plates become less parallel. To my surprise, the drilled balls coming out of the damaged jig are useable until the parallelism is strongly compromised.

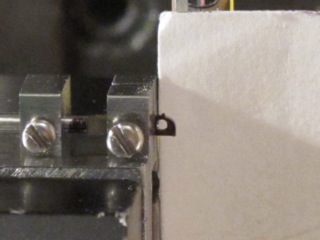

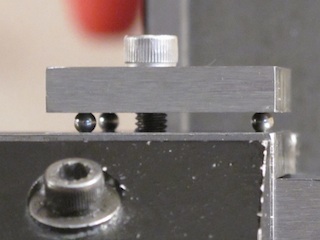

Fig.13: It's very useful to use a ball-nosed hex screwdriver when initially tightening the jig. It allows you to get in at an angle.

Fig.14: The screwdriver doesn't have enough torque to get the jig really tight. For the final quarter turn, you need to use a regular hex key.

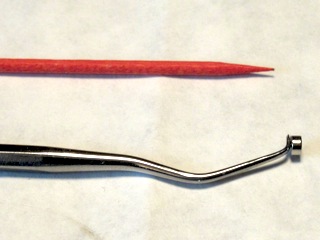

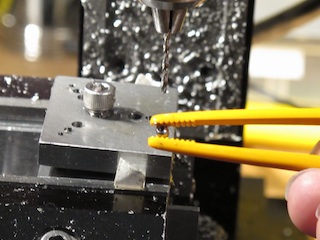

Fig.15: One of my best discoveries for milling has been that you can use a syringe to apply cutting fluid where you need it very precisely. Trying to put oil where you want it with the short spigot of the tin can is messy if not impossible here.

Fig.16: Especially with 1/8" balls, it's difficult to use your big meaty fingers. Tweezers are necessary. Metal tweezers tend to become slightly magnetic, which causes lots of trouble. Using a pair of plastic tweezers works better. Normally I use these for cleaning parts in acid baths… Yet another small detail that saves grief.

posted by sven | permalink | categories: stopmo

June 27, 2011

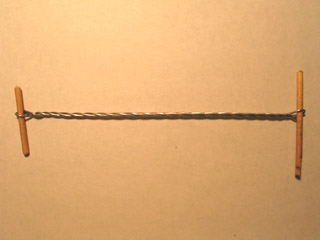

hand paddles

by sven at 11:55 pm

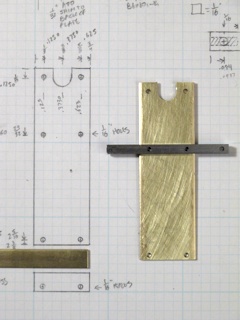

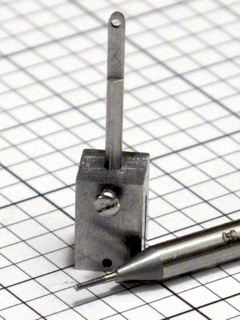

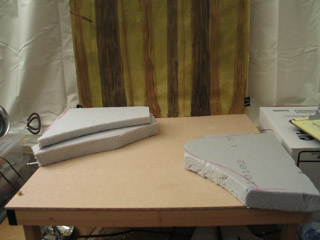

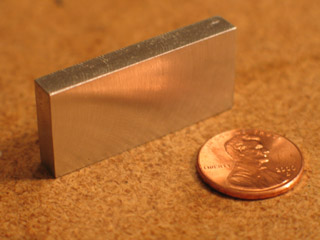

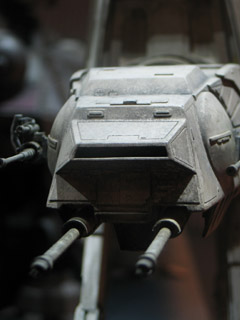

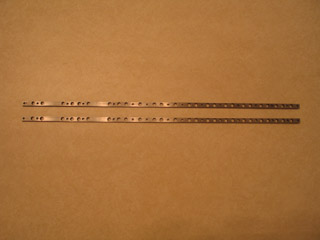

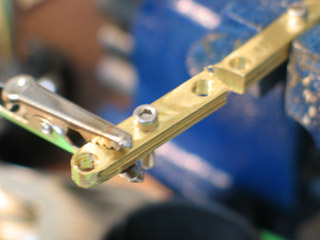

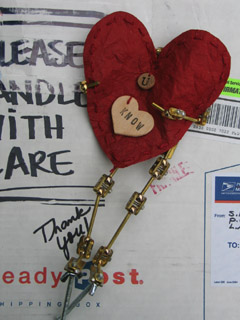

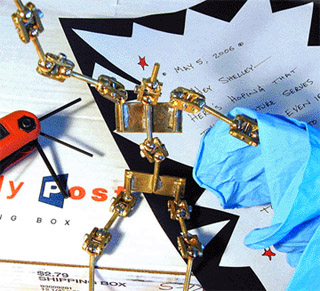

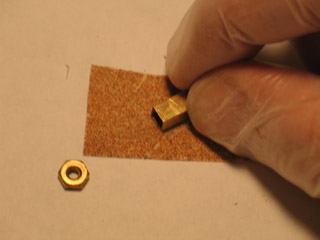

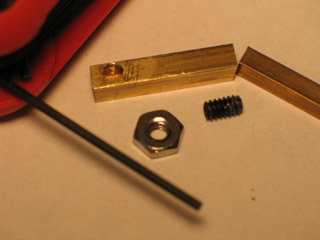

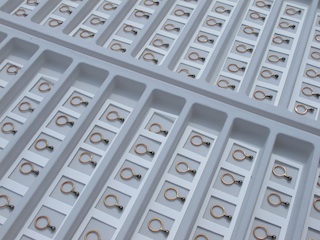

Immediately after the Northwest Animation Festival ended, I got hired to do some armature work for a feature film. I was asked to fabricate 160 puppet hand paddles.

I made parts in two sizes, using 10mm and 8mm jump rings.

The 10mm rings are solid brass. The brazing process draws copper to the surface of the metal, making it reddish in color.

The 8mm ring appeared to be made of brass — but that burned away during brazing, revealing a steel core. I was initially worried that plating would interfere with getting a good bond. It didn't turn out to be a problem.

The balls are 1/8" diameter, the rods 1/16". We're talking SMALL. I constantly had to use needle-nosed electronics tweezers to pick things up.

Doing just about anything 160 times gets tedious. At least the tedium gets punctuated with panic when things go wrong!

Armatures are a love/hate thing. There's a very special misery when things aren't working out in the machine shop… But when things do work, perfect shiny metal is all kinds of sexy.

A couple weeks of living night and day with this project. Then? All those neatly laid out parts get dumped higglety pigglety into bags and I take them off to FedEx, never to be seen again. Good luck in your new life little hand paddles!

posted by sven | permalink | categories: stopmo

February 6, 2011

lipton brisk eminem superbowl commercial

by sven at 10:30 pm

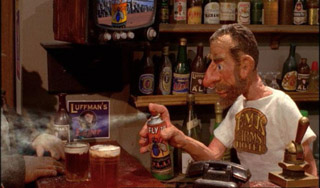

I helped out on a SuperBowl commercial: an ad for Lipton Brisk Tea, featuring Eminem. Big time!

I built the 8" tall armature for one of two Eminem puppets.

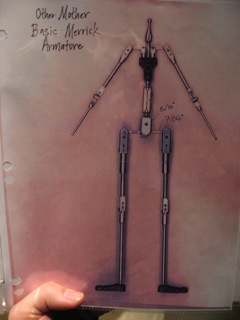

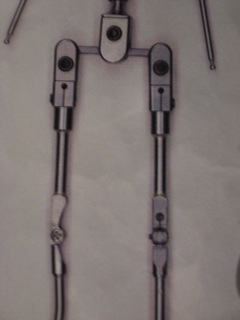

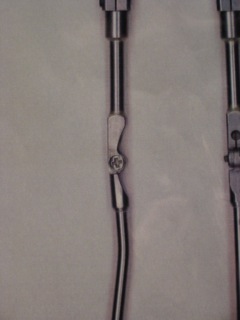

This ad was produced by the San Francisco-based company, Mekanism. Misha Klein directed animation, and Tirsh Hunter was in charge of puppet fab. One puppet was already in progress; my job was to duplicate the original armature, designed by Merrick Cheney.

Understand, Merrick is the living GOD of armature makers. Films like The Nightmare Before Christmas and Coraline... If you need impossibly small, strong, and precise armatures, he's the gold standard. I was thrilled and terrified to try working in his footsteps.

Merrick was able to supply the hinges, which was an enormous help. Due to time constraints, Lionel Ivan Orozco made hands (lots of hands). I understand that Ron Cole did the inner workings of the head. Stepblock joints, swivels, body blocks, assembly... That's all me.

The project took me 16 very sleepless days/nights. My speed, accuracy, and design work all just took enormous strides forward.

But during that time, everything else ceased to exist. I got the armature sent off on December 24... Huge thanks to Gretchin, without whom Christmas would hardly have happened at all!

posted by sven | permalink | categories: exhibits & events, stopmo

January 26, 2011

"mutate" in openlens festival - jan 29

by sven at 11:39 am

My stopmo short Mutate will be showing this weekend in Eugene, Oregon, at the OpenLens Festival.

The date of my film's screening falls between two days when I'm emceeing for PDX Playwrights shows at the Fertile Ground fest. Playwright and animator... It's kinda mind-bending to switch between these identities in such quick succession!

Screening: OpenLens Short Film and Video Competition

Time: 8:00 PM

Location: UO Baker Downtown Center at 325 E. 10th

Admission: $8. Includes screening, awards ceremony, and reception with filmmakers and audience. Refreshments provided by DAVIS Restaurant.A screening of jury selected films for DIVA's OpenLens Festival Short Film and Video Competition will be followed by an awards ceremony and reception at which you can join filmmakers and others in celebrating the evening's showcase of exciting short films. Awards: $500 - Best Of Festival Jury Award. $200 - Honorable Mention Jury Award, and a $100 - Audience Choice Award. A membership in the Mid-Oregon Production Arts Network (MOPAN) organization will be awarded the Best Of The Festival film director.

OpenLens 2011 is a statewide event that provides an opportunity for Oregon short film artists to showcase their work in a competitive event. It is a small festival dedicated to the showcasing of new work while providing the opportunity for artists and audiences to meet and network.

This year’s festival features work from around the state as well as that of local artists. Of the 36 entries submitted, the festival Jury has picked a number of excellent films for the evening program. This year's juried films, trailers, and descriptions are available online.

Update: "Mutate" won Honorable Mention!

posted by sven | permalink | categories: exhibits & events, movies, stopmo

November 13, 2010

birthday party: still 30 something

by sven at 7:00 am

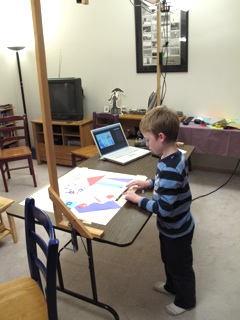

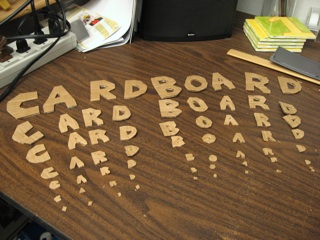

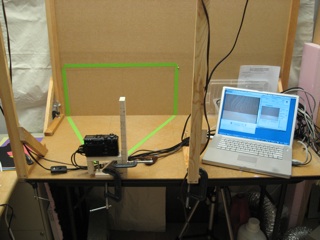

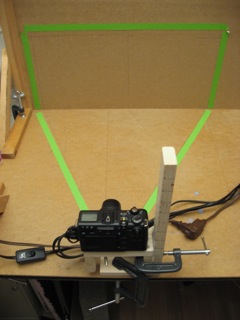

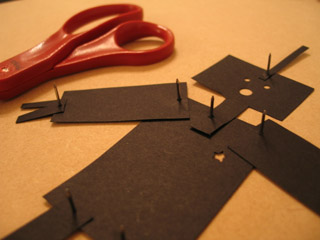

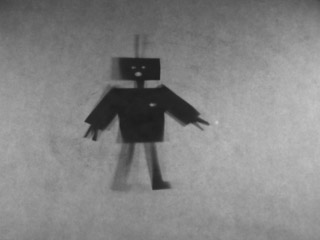

click on image to play film (39sec - 1.9 MB) or view on YouTube Last year I set up a downshooter animation table at my birthday party -- to introduce my friends to this artform that I love. It went so well, I decided to do the same thing again this year!

downshooter I provided colored paper so people could cut out whatever shapes they wanted. A downshooter is very user friendly: just move the shapes around on the table, and hit the computer's "enter" button to shoot a frame.

(My one mistake was that I should have used the DV cam rather than a digital still camera. Though picture quality is lower, it can capture frames faster, which makes the process more fun for everyone.)

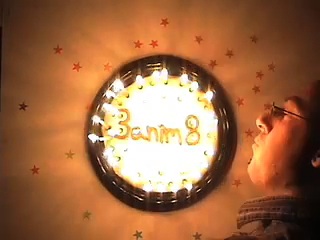

Ben gets animated Most of the animation was done by our friend Ben H. From the very start, he saw the exciting possibilities about what you can put beneath the camera...

Ben tells a story It was remarkable to watch Ben's approach evolve over the course of the evening. If you pay attention, after the cake portion of the film, the images become less random. ...We're watching a story about a wizard who casts a spell!

posted by sven | permalink | categories: exhibits & events, stopmo

November 11, 2010

thirty-nine dance: behind the scenes

by sven at 5:30 pm

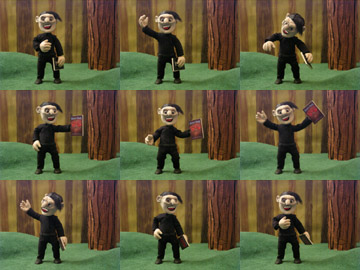

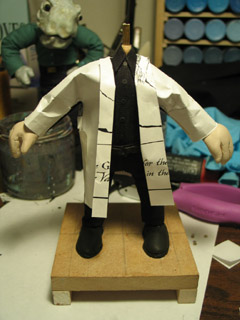

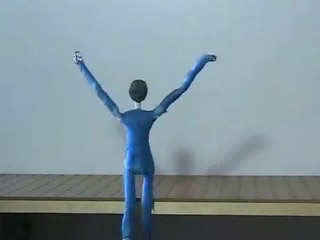

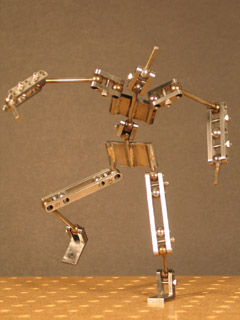

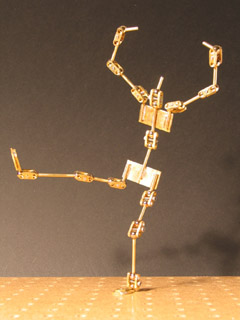

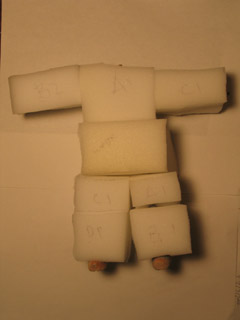

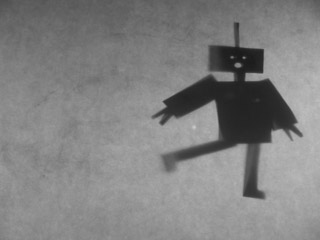

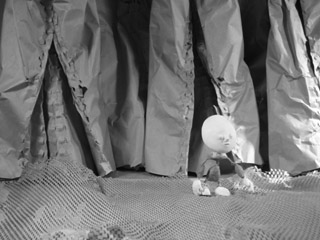

dancing puppet I want to share some "behind the scenes" photos from my most recent stopmo clip, The Thirty-Nine Dance.

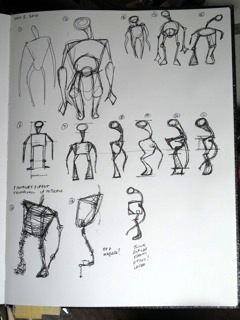

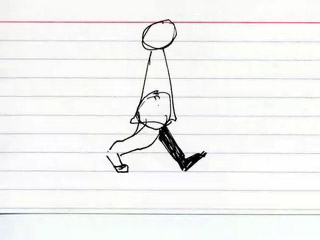

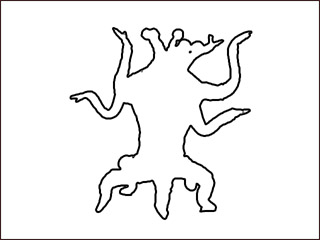

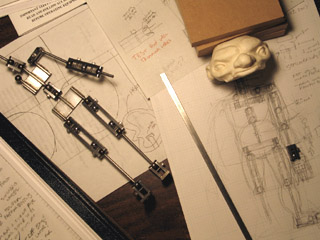

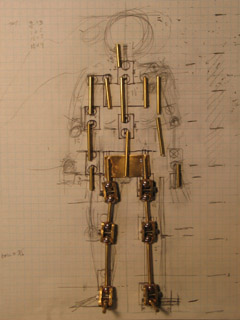

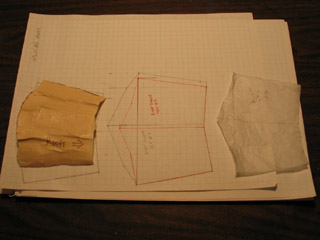

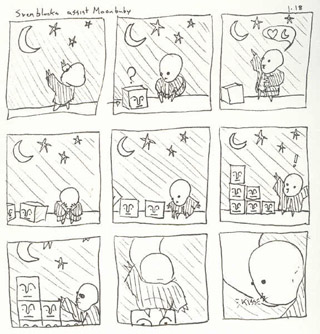

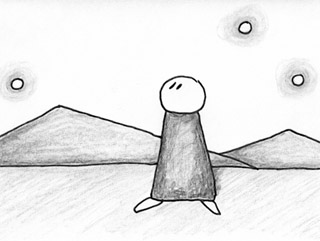

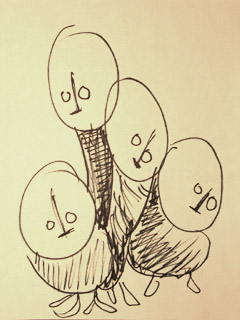

fig.1 sketches Fig.1: For the puppet design, I didn't just want a generic humanoid. I wanted something stylized.

In 2D hand-drawn animation, there's an emphasis on finding the underlying forms of a character. If you're going to draw Donald Duck or Homer Simpson thousands of times, you need to know that the head is built upon a circle, the belly is constructed from a bean, the character is four head-circles tall... Etc.

Using this sort of thinking, I decided to base the body on a squashed square shape, and made the legs almost twice as long as the torso.

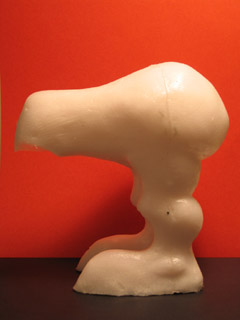

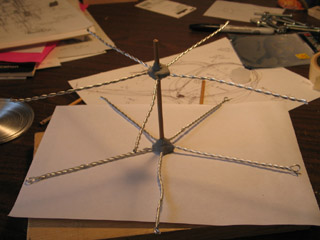

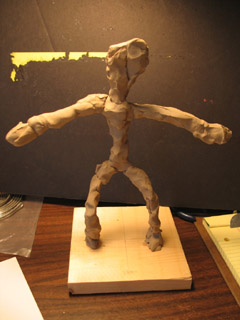

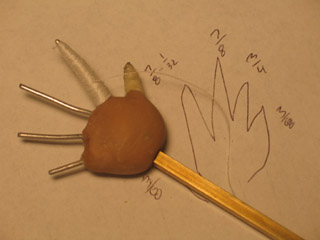

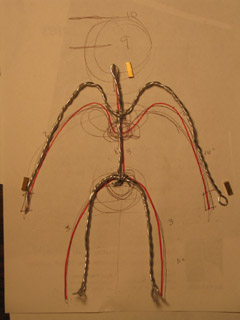

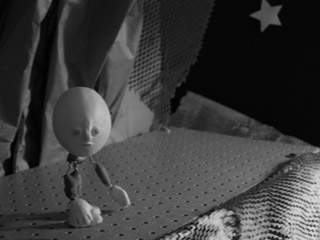

fig.2 maquette armature Fig.2: I want puppets that have a highly sculpted look. So, for the first time, I went ahead and tried making a maquette before creating my final puppet. Seeing a rough sketch in 3D allowed me to identify some changes that I wanted to make in the final design.

Some thoughts about the armature you do your sculpt on...

If you're going to cast a puppet in foam latex or silicone, you can either:

- make an animatable armature, do your sculpting on top of it, and then make a mold, or

- do your sculpt on a rough armature, make a mold, and then make an animatable armature to fit inside it.

While I'm not doing cast puppets yet, I do want to work in the direction of option B. It makes the life of the armature builder more difficult -- but prioritizes creating a dynamic sculpt... Which is, after all, what the audience is going to see.

The armature that you build a sculpt on is different from an armature suited for animation. The maquette armature you see above starts with two equal lengths of wire for the left and right sides of the body, which then get bound together at the spine. This construction helps make sure that both sides of the puppet are symmetrical. The entire thing is then wrapped in a smaller gauge wire, which gives your sculpting material something to grip onto.

fig.3 bulking out with aluminum foil Fig.3: If you look at photos from the making of Return of the Jedi, all the monster maquettes from Jabba's palace appear to be made from water-based clay. If you look at photos from Star Wars Episodes I-III, you can see that maquettes are now made from Super Sculpey brand polymer clay. From what I've read online, Super Sculpey seems to have become Hollywood's default medium for maquettes.

With polymer clay, you want the material be of similar thickness everywhere on the maquette's body so that it will bake evenly. Thick parts of the body (like the torso) get bulked out with aluminum foil. Tip to the thrifty: the Dollar Store is a great place to pick up cheap rolls of foil!

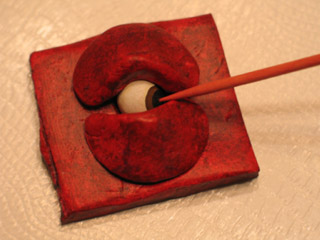

fig.4 Super Sculpey Fig.4: I was imagining that the puppet would be wrapped in sisal twine, burlap, thread, and possibly plant materials. To simulate this texture, I ran the Super Sculpey through a pasta roller, sliced it into fettuccine-like strips, and then wrapped the strips around the armature. For even thinner strands, I used a small clay extruder.

fig.5 finished maquette Fig.5: Paint really transforms a maquette and brings it to life. I gave the maquette a base of black acrylic paint, then dry-brushed highlights with pale blues and greens. (Painting the wooden base black goes a long way toward creating a professional presentation.)

Studying this maquette, it seemed as if I'd lost some of the angularity that I liked so much in the original sketch. Also, I felt that there needed to be some area on the puppet that was smooth, to contrast with the chaotic fibrous areas. I changed my mind about colors, and decided to go with a red palette.

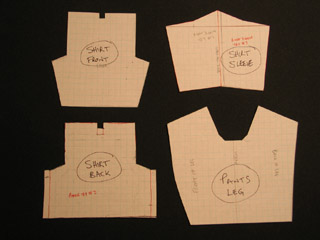

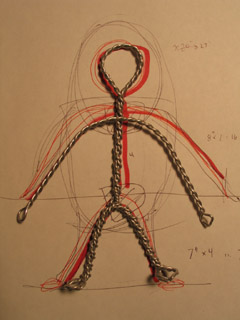

fig.6 puppet armature Fig.6: My original thumbnail sketch was about 2" tall. For the maquette, I blew the sketch up 200% on our photocopier, and made the thing 4" tall. For the final puppet, I went up 200% again, and created an 8" tall puppet. I could have just drawn a new reference sketch that was 8" -- but there tends to be a special vitality in thumbnail sketches, which I wanted to preserve as long as possible in the construction process.

fig.7 wood torso block Fig.7: The torso is made from a scrap of pine wood. I drilled 1/8" diameter holes where the arms, legs, and neck would attach. Then I ground off the edges using both a Dremel moto-tool and a belt sander.

My use of wood here is inspired by the puppets of Nick Hilligoss. One difference is that he sometimes has multiple strands of wire glued into multiple holes -- rather than all being glued into a single hole as a bundle. I can see, at least in theory, that this should have benefits for preventing wire breakage. Wires tend to break where they interface with something hard. Multiple attachment points would give you more safeties.

fig.8 brass feet Fig.8: The feet are made from K&S brand brass, which you can find at most hardware and hobby stores. The feet are 1/4" wide and about 5/8" long. I tapped the tie-down holes to receive 4-40 threaded rods. Rather than have the square tubing point upward, I have it come out the back of the foot. I think that this better simulates an ankle joint, putting it close to the ground, rather than a ways up the leg. (Again, this approach to ankles was inspired by Nick Hilligoss.)

fig.9 untwisted aluminum wire limbs Fig.9: Most amateur stopmo puppet makers twist strands of wire to make a sort of cable. In recent years, the default approach in some Hollywood-based stopmo houses is to leave wires untwisted -- instead binding them together with thread and a coat of Barge brand flexible cement.

An advantage of leaving wires untwisted is that it avoids putting tension into the wires, which could cause breakage. Also, for an area like the puppet's neck, where you rotate left and right, you can feel twisted wire tightening or loosening depending on which way you rotate... That doesn't happen with untwisted wire.

A disadvantage of leaving wires untwisted is that you can sometimes hear the wires sliding past each other, when they bend at the hip or elbow.

Based on personal study, I think that different wire strategies may be better suited to different parts of a puppet body -- depending on whether a bend or a twist motion is most common...

See, there are actually three options for working with strands of wire: (a) untwisted, (b) twisted, and (c) coiled. For coiled wire, you wrap your wires horizontally around a vertical core wire. Think about what happens when you bend a spring or slinky at a 90 degree angle -- very little stress is put on the wire.

In theory, it could be smart to put a coiled strand or two in at the puppet's knees -- as safeties, in case the core untwisted wires break. In practice, however, it seems like a lot of trouble to try to come up with a perfect solution for what is, after all, only a wire puppet.

For the dancer puppet, I decided to go with four untwisted strands of 1/16" dia. annealed aluminum wire for all limbs. Barge is very toxic, and working with thread is awkward... So I bound the strands together using flexible vinyl electrical tape. It seems to have worked quite well for this build-up puppet -- but I recognize that there might be adverse chemical reactions if I were to bake these bundles inside of foam latex.

fig.10 bulking out with rigid foam Fig.10: The initial armature looked a bit too much like a bar of soap with legs. So, I bulked out the torso with rigid insulation foam, to give it some additional form. Insulation foam is wonderfully easy to carve, and is easily adhered using hot glue.

I should also mention that I wanted to give the lower legs some "bones"... Rather than use plumber's epoxy putty (as I have in the past), I stiffened the lower legs by wrapping them in a thin gauge steel wire. The difference in flexibility between the top and bottom of the leg was plenty enough to help me animate the illusion of there being stiff bones there.

The head has a wooden core, bulked out with aluminum foil, and a thin Super Sculpey skin, which I sanded down for maximum smoothness.

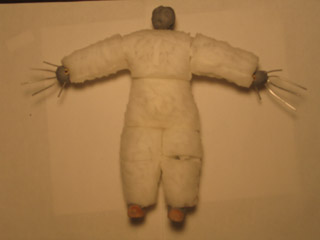

fig.11 wrapping with twine Fig.11: For skin-level texture, I wrapped the puppet in sisal twine, periodically laying down a dab of hot glue to keep it in place. At the maquette stage, I thought that I'd have organic textures going in all directions... But the look of the methodical wrapping was so striking, I decided to just stick with that.

fig.12 wrapping complete Fig.12: I'm very pleased with the look of the wrapped sisal. However, at this point I discovered a down side. The twine greatly reduced flexibility -- particularly at the shoulders and hips, where the wrapping is thickest.

I also discovered a big flaw in the armature's design. In a human skeleton, the base of the pelvis is significantly lower than the points where the femurs connect. The head of a femur really connects to the side of the pelvis, not the bottom...

In my armature, I have the leg wires shooting straight out the bottom of the torso block. Consequently, it seems like the bend is part way down the leg -- not up at the hip. In future designs, I intend to have the leg wires come out the sides of the pelvis... And I'll look at carving the pelvis to be shaped more like a triangle, rather than a box.

fig.13 base of black acrylic paint Fig.13: As with the maquette, I started painting the puppet by laying down a base coat of black acrylic paint. Sisal is absorbent, so I watered the paint down a lot, to help it soak in.

fig.14 finished puppet Fig.14: Even after applying the base of black acrylic, the puppet had a lot of loose fibers sticking off of it. I used an electric razor to trim them down some. Then, I coated the puppet in a 50-50 mix of balloon rubber and black acrylic to hold the whole thing together. Painting was finished off with a dry-brushed layer of red acrylic, and another thin layer of orange (no balloon rubber this time).

fig.15 tie-downs Fig.15: For tie-downs, I used what I always use: 3" long 4-40 threaded rods, purchased at Ace Hardware. The feet are tightened into place using brass thumb screws. Tightening these is actually really hard on my fingers... I'm interested in replacing them with something more friendly, like wing nuts.

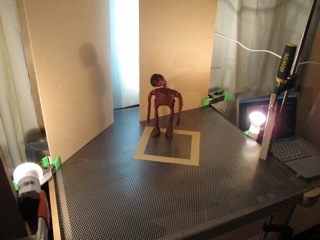

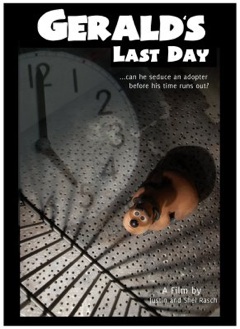

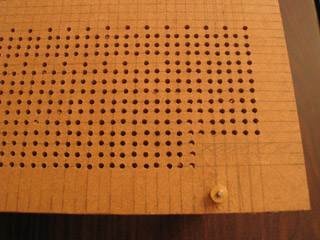

The stage for this project is a sheet of perforated steel that I bought a few years ago from onlinemetals.com. The convenience of having all those holes pre-drilled can't be beat. I know a number of stopmoes have imitated Justin Rasch, who drilled hundreds of holes by hand in the floor of the set for his film Gerald's Last Day... I tried that myself once -- but for the size of the stage floor I wanted, the monotony was unbearable. I think I paid about $50 for the perforated steel. It was money well spent.

One down-side of a steel floor, though: Unlike MDF, it has no give to it. To fix a puppet foot in place, you actually have to tighten the tie-down nut really hard. To make it easier on myself, I added rubber washers to the tie-downs, underneath the set. That helped some -- though not as much as I'd like.

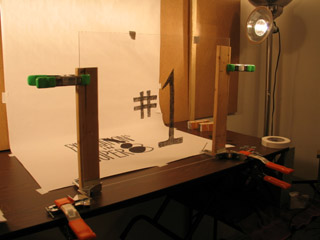

fig.16 lighting - view 1 Fig.16: I always forget how painful it is trying to find a lighting set-up that works. For this project, I wanted to imitate lighting at dance performances -- which often comes in from the sides, helping to define the dancers' muscles.

fig.17 lighting - view 2 Fig.17: For my stopmo films so far, I've generally flooded the stage with as much diffused light as possible, bouncing beams off of the ceiling and white photographers' umbrellas. I'm trying to get away from that approach; instead, setting up just a few lights that perform precise jobs.

I've discovered that Home Depot sells light sockets for $2 that are just a socket and a plug with no cord. Very useful for trying out different lights! I'm using (if I recall) two little 40 watt bulbs at the front of the stage: one at the puppet's eye level that comes from the front, and one that's more at hip level, that comes strongly from the side (and casts a nice shadow on the wall).

I would have been blinded by the side lamp, so I clamped a piece of wood between me and it to protect my eyes. In the future, I'm interested in seeing if I can modify tin cans to narrow the beams of light.

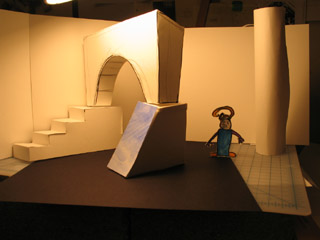

fig.18 lighting - view 3 Fig.18: I was very pleased with the idea of having two unconnected flats that let you see another wall beyond them. So much amateur stopmo work just sticks the puppet in the corner of a cubical room -- or worse yet, against a flat wall. I really want to create some sense of depth in my sets.

The rear plane was lit with a strip of LED lights. I'm excited about LEDS -- they don't get hot, they're energy efficient... I've tinkered with wiring LEDs purchased at Radio Shack -- but haven't got the hang of it yet... And I'm uncertain about how to give them a stable power supply.

One happy accident was that the LEDs are more blue than the incandescent lights. The variation in color added interest to the set.

fig.19 hanging camera Fig.19: The camera is a PowerShot G5, attached to a manfrotto geared head. Tripods are a nightmare; if you accidentally kick them, your shot is ruined. So I hung the camera upside-down from overhead. My framegrabber software, Dragon Stop Motion, makes it incredibly easy to flip the image right-side-up again.

fig.20 camera close to subject Fig.20: I've spent a lot of time during the past two years trying to better understand how a camera's "angle of view" impacts stopmo work.

When the camera is not zoomed in at all, you have the widest angle of view. You can get the camera close in to the set -- which can be important if you don't have much floor space in your studio for a camera tripods and such.

Having the camera so close to the puppet can also create some "perspective distortion"... Increased foreshortening and some slight fisheye-like curvature around the edges of the frame. This helps create some sense of depth.

fig.21 camera far from subject Fig.21: In the previous photo, the camera was about 12" from the puppet. In this photo, the camera is maybe 72" back. The foreshortening is gone, and the image looks fairly flat.

However, I also don't need as much backdrop... When the angle of vision is narrower, the rear wall or sky cyclorama doesn't need to be as wide.

So there's a trade-off to be made:

- When the camera is very close to the puppet, you're going to need a wide backdrop. (big X-axis)

- When the camera is farther back, you can have a narrow backdrop -- but you'll simultaneously need more space for pulling the camera back. (big Z-axis)

My compromise was to put the camera about 24" back from the puppet. I don't get as much foreshortening as I'd like -- but both the width of the backdrop and the placement of the camera were manageable, given the size of my work room.

fig.22 camera support frame Fig.22: I've built several wooden pylons that I can move around at will, clamping them to the edge of tables. For my film Mutate, the camera was clamped to a cross strut that was attached to the animation table itself. For this project, I created an 8-foot-wide arch that was attached to two separate tables on either side of the room.

I am totally enamored with this modular approach. It's great to be able to quickly set up different arrangements as need arises. Which leads to Sven's rule: YOU CAN NEVER HAVE TOO MANY C-CLAMPS!

One downside of the big arch concept, though, was that if the animation table moved even slightly, it's the same as kicking a tripod. If you watch closely, in the film you can see that the entire set moves about a millimeter backwards.

For my next film, I think I'm going to try creating a stable wooden cage around the set, and then have the camera extend outward on some sort of pole -- so that if the animation table moves, the camera will have to move with it.

fig.23 hot set! Fig.23: It's a different feeling animating when you're using a few well-positioned point lights, rather than flooding the whole room with diffused light. Most of the room is in darkness. I've seen that professional stopmo sets tend to have black curtains surrounding the animation area... It's a pleasing feeling to begin reproducing that environment at home.

posted by sven | permalink | categories: stopmo

November 7, 2010

thirty-nine dance

by sven at 11:21 am

click on image to play film (5sec - 1.7 MB) or view on YouTube For my birthday, I took a "staycation" in the studio. For a few days, I got to eat, breath, and sleep stopmo.

I've been wanting to try choreographing a puppet dance. I managed to build a new puppet, compose a song, and work out some steps. Time ran short, though, so I only got five seconds on film.

If you want to hear the complete "thirty-nine" song, you can listen to the mp3 here.

(Note: The song has a very low bass line, which might not be audible on some computer speakers.)

posted by sven | permalink | categories: music, stopmo

October 12, 2010

"mutate" in film festivals

by sven at 5:16 pm

In the next few days, my film Mutate will be playing at three different film festivals...

Astoria International Film Festival

Saturday, Oct 16

1:00pm

Liberty Theater

1203 Commercial Street

Astoria, OR 97103

(503) 325-5922"In this brief but highly creative abstract clay animation, we witness the whimsical and even sometimes intriguingly edgy musings of a sculptor/animator with a sense of humor. The zany sound track mirrors the outré visuals. Like most art, Mutate defies concrete analysis; just relax and enjoy the quirky fun!"

-- Michael Fendel, Astoria International Film Festival

Salem Film Festival

Saturday, Oct 16

3:00pm - Northwest Emerging Artists Shorts Package

The Grand Theater

191 High Street NE

Salem, OR 97301

(503) 990-0150"Strange clay creatures revolve, dissolve and evolve in this delightfully quirky stop-motion animation."

-- SFF website

Video Gong Show - Final Round

Thursday, Oct 21

8:00pm ???

4122 N.E. Sandy Blvd

Portland, OR 97212

(503) 281-4215"3 competitive rounds of screenings have been scheduled & each is to take place in a different Portland quadrant throughout the summer. Top 5 films from each round will advance to the Finals at the Hollywood Theatre in October. Contestants compete for a $100 cash prize and a grand prize package from Picture This worth $1000. Just as with the classic show, the film's run time could be cut short by the sound of a GONG! The competition is meant to be fun (not cruel). Come support Portland's Indie filmmakers, while sipping a beer and having a laugh."

-- Film Action Oregon website

Why, yes -- AIFF and SFF do happen on the exact same day. Sigh. I'll be at the Salem screening if you want to see me in person.

Slim hopes of winning the Video Gong Show... In round 1, I was a runner up. I only moved on to the finals after someone else's film got disqualified.

Even so: Very exciting to be taking my filmmaking to the next level -- getting out there, getting seen!

posted by sven | permalink | categories: exhibits & events, movies, stopmo

July 13, 2010

making a replacement face kit

by sven at 3:45 am

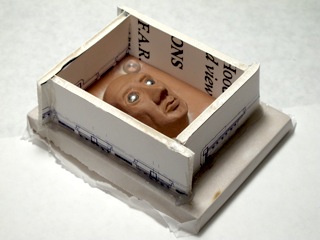

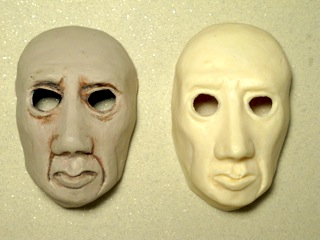

I've discussed mold design for my film, The Beginning. In this post I'll document how you take resin castings and turn them into a full replacement face kit.

fig.1 replacement face kit Fig.1: The mouths in my face kit are based on the visemes described in Preston Blair's classic book, Cartoon Animation. Every other set of mouth shapes I've encountered in books and online is derivative of Blair's seminal work. Many authors simplify Blair's shapes in ways that I consider mistakes; for instance, identifying vowels by alphabet letter rather than phonetic sound. For my purposes, I decided I could simplify the set very slightly and get away with 12 mouth shapes.

Problem: How do you name these mouth shapes? —Particularly the vowels? I decided for this project to do some in-depth research on how dictionary pronunciation guides spell out phonemes. The wikipedia entry on Pronunciation respelling for English proved extremely helpful… To my surprise, it turned out that there is no universal system! One system may define "ay" as sounding like pay — whereas another defines it as sounding like pie.

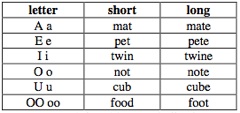

For my purposes, I decided that a simple and elegant approach would be to denote long vowels with capital letters, and short vowels with lower case letters. One additional vowel is required, though: OO/oo. Here's my pronunciation guide:

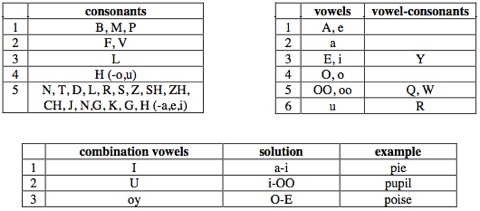

I also found it useful to reorganize the various phonetic sounds into four categories… Consonants, vowels, consonants that use vowel mouth shapes, and vowel sounds that are actually made by combining two other letters' sounds. Here's my cheat sheet:

Now that you understand how I've chosen to notate and organize phonemes, here's the list of the 12 mouth shapes I finally settled on:

- A e

- a

- BMP

- E i Y

- FV

- H(-o,u)

- L

- neutral

- O o

- OO oo QW

- u R

- X

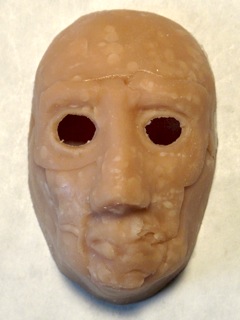

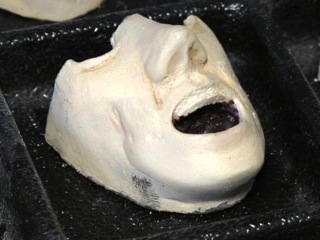

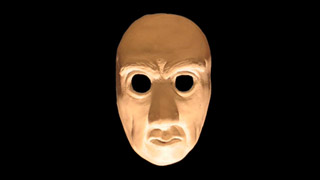

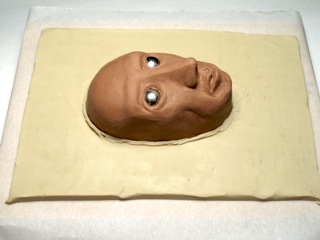

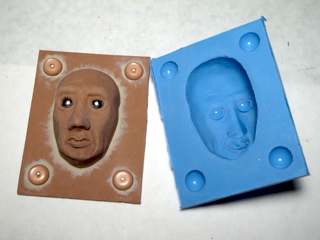

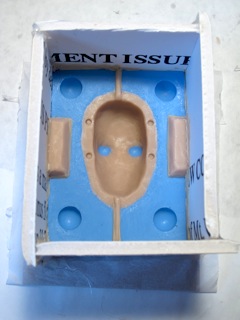

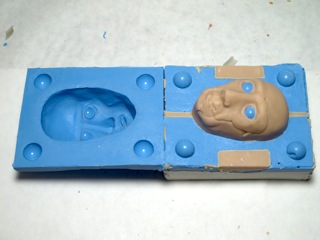

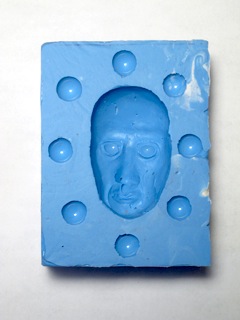

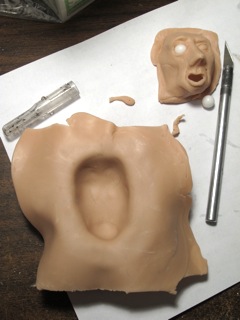

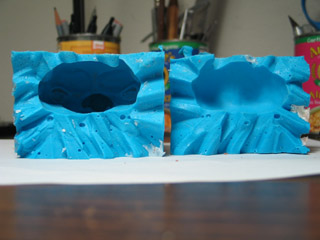

fig.2 casting cut in two Fig.2: I had originally planned to do the replacement faces as single-piece masks. The problem with that plan, though, is that eyebrows would have to be re-applied every time the mouth moves. No good! So I decided to try the method used in Coraline: doing the forehead and lower face as two separate pieces.

I took a casting and cut it in half with a craft saw. The forehead gets discarded. I used a belt sander to smooth the rough edges of the lower face and make them perfectly flat.

fig.3 placeholder in mold Fig.3: The half-face part I just made goes into the mold as a placeholder. I use a brush to thoroughly paint the part with vaseline, then do a casting of just the forehead, which will be a second placeholder. The two parts match up exactly now. Had I used the forehead piece that was cut off in fig.1, seams would have been much wider.

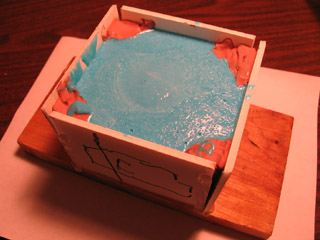

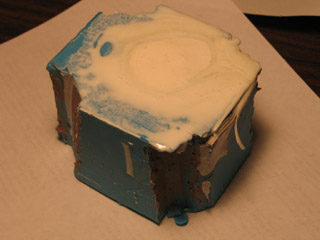

fig.4 tray for chemical work Fig.4: Working with silicone, polyester resin, and solvents is nasty, messy, and toxic. In addition to wearing my usual safety gear, I purchased a large metal tray from a restaurant supply store, on which to do all my chem work.

To make cleanup easier, I tried lining the pan with wax paper. Unfortunately, chemicals go right through it. In the future, I may try laying down Saran wrap or something similar instead.

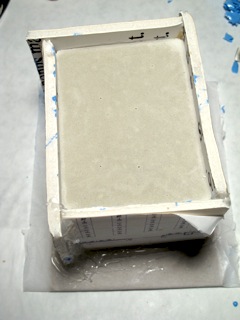

fig.5 casting with polyester resin Fig.5: For casting the mouth and forehead pieces, I found that 10ml of part A combined with 10ml of part B gave me about the right volume. You need to have some overflow that will exit though the sprue holes in order to get a good casting. The area around the mold gets progressively messier with each casting.

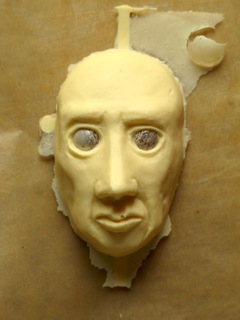

fig.6 castings Fig.6: It takes at least an hour for the resin to fully cure. I found that the pieces were firm enough to demold at 30 minutes. Do not trim off flashing at that point, however — the curved casting is likely to get deformed by your grip while you work on it.

It took 15-20 minutes to release each casting, clean the mold, and pour in another batch of resin. So turn-around time for each part was about 50 minutes. Needing to make 12 mouths, 3 foreheads, and some spare parts to have on hand, this was more than 2 solid days of work.

It was a fairly frustrating part of the fabrication process… Not because I had to wait, per se — but because I had to repeatedly take off the gloves to work on a B project, then interrupt myself to put the gloves back on when the each new casting was ready. No sense of flow was possible. It would be preferable to be working on two casting processes simultaneously, to avoid switching gears so much.

fig.7 wear and tear Fig.7: In all, I got 24 good castings out of the mold before wear and tear got too bad. Studying the mold interior, I think I see what went wrong. When I made the mold, I painted a thin detail layer of silicone onto the sculpt, then covered that with a thicker layer. Bubbles were trapped between the thin skin and the thicker one… So most damage was from the thin skin tearing away to reveal the air bubble trapped behind it. Use of silicone thinner probably also helped weaken the material.

fig.8 flexible shaft Dremel Fig.8: We don't need a set of identical faces — we need them resculpted with different mouth shapes and eyebrow positions. For this job, I tried a flexible shaft attachment with my Dremel roto tool for the first time. I was pleased — it was much easier to wield the tool while carving.

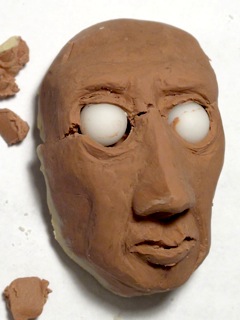

fig.9 carving resin Fig.9: Resculpting a face involves carving away excess material…

fig.10 epoxy clay added - mouth Fig.10: After excess material's been removed, new bits can be built up by adding epoxy clay. I used Magic Sculp, which has about a 4 hour cure time. Apoxie and Milliput are roughly equivalent leading brands.

fig.11 epoxy clay added - brow Fig.11: Eyebrows didn't require any carving. They just sit on the forehead.

fig.12 measuring out epoxy clay Fig.12: Using such tiny quantities of epoxy while sculpting, getting equal proportions of part A and part B can be tricky. I found it useful to flatten out dabs of epoxy on a piece of gridded paper and then use the guide lines to help me cut them to size. (Good free graph paper PDFs are available from incompetech.com.)

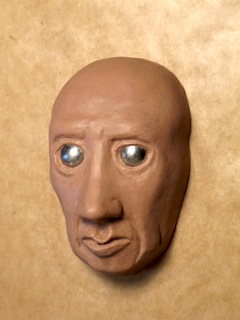

fig.13 registration test Fig.13: Are the face kit pieces working out? As an initial test, put the pieces back onto the interior mold face. I was pleased at this point to see that registration's pretty accurate.

Now we can proceed to making a base for the faces.

fig.14 Super Sculpey pressed into mold Fig.14: During the mold-making process, I made a Super Sculpey placeholder to establish the thickness of the faces. When it comes time to make a base for the faces, the Sculpey piece becomes useful again.